Michelangelo

Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

Michaelangelo Buonarroti—Sculptor, Painter

March 6, 1475, Caprese, Italy, 1:30 AM, LMT or 1:45 AM, LMT (Source: 1:30, Fagan; 1:45, The Life of Michaelangelo, by Ja.A.Symonds) Died, February 18, 1564, Rome, Papal States.

“Circle Book quotes J.A.Symonds, ‘The Life of Michelangelo,’ in which the child's father wrote in his notebook, ‘A male child was born to me on Monday morning (March 6 OS) four or five hours before daybreak’ (LMR computes sunrise as 6:15 AM)”

(Ascendant, Sagittarius; Sun conjunct Mars in Pisces with Moon also in Pisces conjunct Mercury in Aquarius; Mercury and Jupiter in Aquarius; Venus in Aries; Saturn in Cancer; Uranus and Neptune in Scorpio; Pluto in Virgo)

Michaelangelo was one of the great geniuses of all time. He is known chiefly as a sculptor (the David), and as the painter of the frescoes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome. Like Leonardo, he had Sagittarius as his Ascendant and a fourth ray soul. However, his personality ray was very likely, ray six, reinforced by the Sun conjunct Mars in sixth ray Pisces with the Moon also in Pisces. The three signs through which the sixth ray passes, constellationally (Virgo, Sagittarius and Pisces) all have planets or are prominent in the chart.

Pisces bestows upon Michelangelo his tremendous sensitivity and imagination. Venus in Aries, his instant and unrestrainable enthusiasm for beauty. Jupiter in Aquarius, orthodox ruler of the Ascendant, indicates his profound affect upon the culture (Aquarius) of Italy and of the world. The Mercury Moon conjunction shows the ingenious skill (Mercury in Aquarius) with which he was able to execute his deep subjective and imaginative impulses (Moon in Pisces). Saturn in Cancer trine the Mars/Sun conjunction in Pisces, conferred his ability to regulate his impulses and bring form (Saturn and Cancer) to perfection. Pluto in Virgo assisted this, as he knew exactly what to eliminate to bring his sculpture forth from the stone in which they were encased. Both his prodigious power to envision and his unparalleled achievements in the field of religious art are indicated by Sagittarius (which is the soul sign of religious Italy). His extraordinary execution of the art which represented Catholic Theology can be seen by his ninth house Pluto in Mercury square his Sagittarius Ascendant and opposing his Sun/Mars conjunction in Pisces. The elevated Pluto contributed to the “Last Judgment”

Michelangelo, a man of great intensity and enthusiasm, had an undying passion for beauty. Interestingly, his rays, proposed as the fourth and the sixth, are exactly those of Italy—however reversed, as Italy has a sixth ray soul and a fourth ray personality.

A beautiful thing never gives so much pain as does failing to hear and see it.

A man paints with his brains and not with his hands.

(Sun in 3rd house)After four tortured years, more than 400 over life-sized figures, I felt as old and as weary as Jeremiah. I was only 37, yet friends did not recognize the old man I had become.

Already at 16, my mind was a battlefield: my love of pagan beauty, the male nude, at war with my religious faith. A polarity of themes and forms - one spiritual, the other earthly.

Beauty is the purgation of superfluities.

Death and love are the two wings that bear the good man to heaven.

Faith in oneself is the best and safest course.

Genius is eternal patience.

Good painting is the kind that looks like sculpture.

I am a poor man and of little worth, who is laboring in that art that God has given me in order to extend my life as long as possible.

I am still learning.

(Sagittarius Ascendant)I cannot live under pressures from patrons, let alone paint.

(Pisces Sun conjunct Mars)I feast on wine and bread, and feasts they are.

I hope that I may always desire more than I can accomplish.

(Sagittarius Ascendant)I live and love in God's peculiar light.

I live in sin, to kill myself I live; no longer my life my own, but sin's; my good is given to me by heaven, my evil by myself, by my free will, of which I am deprived.

I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.

If in my youth I had realized that the sustaining splendour of beauty with which I was in love would one day flood back into my heart, there to ignite a flame that would torture me without end, how gladly would I have put out the light in my eyes.

If it be true that any beautiful thing raises the pure and just desire of man from earth to God, the eternal fount of all, such I believe my love.

If people knew how hard I worked to get my mastery, it wouldn't seem so wonderful at all.

If we have been pleased with life, we should not be displeased with death, since it comes from the hand of the same master.

It is better docration when, in painting, some monstrosity is introduced for variety and a relaxation of the sense and to attract the attention of mortal eyes, which at times desire to see that which they have never seen.

It is necessary to keep one's compass in one's eyes and not in the hand, for the hands execute, but the eye judges.

(Pluto in Virgo in 9th house opposition Sun & Mars)Many believe - and I believe - that I have been designated for this work by God. In spite of my old age, I do not want to give it up; I work out of love for God and I put all my hope in Him.

My soul can find no staircase to Heaven unless it be through Earth's loveliness.

The greater danger for most of us lies not in setting our aim too high and falling short; but in setting our aim too low, and achieving our mark.

The greatest artist has no conception which a single block of white marble does not potentially contain within its mass, but only a hand obedient to the mind can penetrate to this image.

The more the marbles wastes, the more the statue grows.

The power of one fair face makes my love sublime, for it has weaned my heart from low desires.

The true work of art is but a shadow of the divine perfection.

There is no greater harm than that of time wasted.

Trifles make perfection, and perfection is no trifle.

What do you despise? By this you are truly known.

What good I have comes from the pure air of your native Arezzo, and also because I sucked in chisels and hammers with my nurse's milk.

What spirit is so empty and blind, that it cannot recognize the fact that the foot is more noble than the shoe, and skin more beautiful than the garment with which it is clothed?

“Every block of stone has a statue inside it and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it” quote

“The promises of this world are, for the most part, vain phantoms; and to confide in one's self, and become something of worth and value is the best and safest course.” quote

“The best artist has that thought alone Which is contained within the marble shell; The sculptor's hand can only break the spell To free the figures slumbering in the stone” quote

“Every beauty which is seen here by persons of perception resembles more than anything else that celestial source from which we all are come.” quote

“I have never felt salvation in nature. I love cities above all.” quote

“Everything hurts.” quote

(Saturn in Cancer. Sun in Pisces.)“It is well with me when only when I have a chisel in my hand” quote

“Carving is easy, you just go down to the skin and stop” quote

“Painters are not in any way unsociable through pride, but either because they find few pursuits equal to painting, or in order not to corrupt themselves with the useless conversation of idle people, and debase the intellect from the lofty imaginations in which they are always absorbed.” quote

“The power of one fair face makes my love sublime, for it has weaned my heart from low desires.” quote

Birth name Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni

Born March 6, 1475

near Arezzo, in Caprese, Tuscany

Died February 18, 1564

Movement High Renaissance di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (March 6, 1475 – February 18, 1564), commonly known as Michelangelo, was an Italian Renaissance painter, sculptor, architect, poet and engineer. Despite making few forays beyond the arts, his versatility in the disciplines he took up was of such a high order that he is often considered a contender for the title of the archetypal Renaissance man, along with his rival and fellow Italian Leonardo da Vinci.Michelangelo's output in every field during his long life was prodigious; when the sheer volume of correspondence, sketches and reminiscences that survive is also taken into account, he is the best-documented artist of the 16th century. Two of his best-known works, the Pietà and the David, were sculpted in his late twenties to early thirties. Despite his low opinion of painting, Michelangelo also created two of the most influential fresco paintings in the history of Western art: the scenes from Genesis on the ceiling and The Last Judgement on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel in Rome. Later in life he designed the dome of St Peter's Basilica in the same city and revolutionised classical architecture with his invention of the giant order of pilasters.

Uniquely for a Renaissance artist, two biographies were published of Michelangelo during his own lifetime. One of them, by Giorgio Vasari, proposed that he was the pinnacle of all artistic achievement since the beginning of the Renaissance, a viewpoint that continued to have currency in art history for centuries. In his lifetime he was also often called Il Divino ("the divine one"), an appropriate sobriquet given his intense spirituality. One of the qualities most admired by his contemporaries was his terribilità, a sense of awe-inspiring grandeur, and it was the attempts of subsequent artists to imitate Michelangelo's impassioned and highly personal style that resulted in the next major movement in Western art after the High Renaissance, Mannerism.

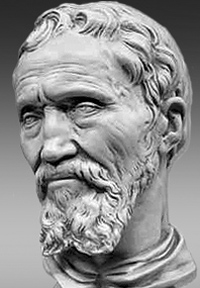

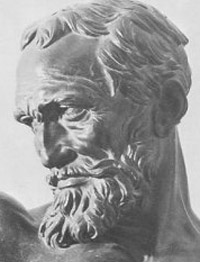

Bust of Michelangelo on the roof of St Peter's Basilica, RomeMichelangelo was born in Caprese near Arezzo, Tuscany. His father, Lodovico di Leonardo di Buonarotti di Simoni, was the resident magistrate in Caprese and podestà of Chiusi. His mother was Francesca di Neri del Miniato di Siena. The Buonarroti descended from Countess Matilda of Tuscany, the family was considered minor nobility. However, Michelangelo was raised in Florence and later, during the prolonged illness and after the death of his mother, lived with a stonecutter and his wife and family in the town of Settignano where his father owned a marble quarry and a small farm. Michelangelo once said to the biographer of artists Giorgio Vasari, What little good I have within me came from the pure air of your native Arezzo and the chisels and hammers.

Against his father's wishes and after a period of grammatics studies with the humanist Francesco da Urbino, Michelangelo continued his apprenticeship in painting with Domenico Ghirlandaio and in sculpture with Bertoldo di Giovanni. Michelangelo's father was able to get Ghirlandaio to pay the young artist, which was unheard of at the time. In fact, most apprentices paid their masters for the education. Impressed, Domenico recommended him to the ruler of the city, Lorenzo de' Medici, and Michelangelo left his workshop in 1489. From 1490 to 1492, Michelangelo attended Lorenzo's school and was influenced by many prominent people who modified and expanded his ideas on art, following the dominant Platonic view of that age, and even his feelings about sexuality. It was during this period that Michelangelo met literary personalities like Pico della Mirandola, Angelo Poliziano and Marsilio Ficino.

In this period Michelangelo finished Madonna of the Steps (1490–1492) and Battle of the Centaurs (1491–1492). The latter was based on a theme suggested by Poliziano and was commissioned by Lorenzo de Medici. After the death of Lorenzo on April 8, 1492, for whom Michelangelo had become a kind of son, Michelangelo quit the Medici court. In the following months he produced a Wooden crucifix (1493), as a thanksgiving gift to the prior of the church of Santa Maria del Santo Spirito who had permitted him some studies of anatomy on the corpses of the church's Hospital. Between 1493 and 1494 he bought the marble for a larger than life statue of Hercules, which was sent to France and disappeared sometime in the 1700s. He could again enter the court on January 20, 1494, Piero de Medici commissioned a snow statue from him. But that year the Medici were expelled from Florence after the Savonarola rise, and Michelangelo also left the city before the end of the political upheaval, moving to Venice and then to Bologna. He did stay in Florence for a while hiding in a small room underneath San Lorenzo that can still be visited to this day. There are still some charcoal sketches on the walls which Michelangelo drew from his memory.

Here he was commissioned to finish the carving of the last small figures of the tomb and shrine of St. Dominic, in the church with the same name. He returned to Florence at the end of 1494, but soon he fled again, scared by the turmoils and by the menace of the French invasion.

He was again in his city between the end of 1495 and the June of 1496: whereas Leonardo da Vinci considered the ruling Savonarola a fanatic and left the city, Michelangelo was touched by the friar's preaching, by the associated moral severity and by the hope of renovation of the Roman Church. In that year a marble Cupid by Michelangelo was treacherously sold to Cardinal Raffaele Riario as an ancient piece: the prelate found out that it was a fraud, but was so impressed by the quality of the sculpture that he invited the artist to Rome, where he arrived on June 26, 1496. On July 4 Michelangelo started to carve an over-life-size statue of the Roman wine god, Bacchus, commissioned by Cardinal Rafaelle Riario; the work was rejected by the cardinal, and subsequently entered the collection of the banker Jacopo Galli, for his garden.

In 1492, Lorenzo de' Medici died. Michelangelo then studied anatomy with the help of the Prior of the Hospital of Sto Spirito, for whom he appears to have carved a wooden crucifix for the high altar. A wooden crucifix found there (now in the Casa Buonarroti) has been attributed to him by some scholars. The next few years were marked by the expulsion of the Medici and the gloomy Theocracy set up under Savonarola, but Michelangelo avoided the worst of the crisis by going to Bologna and, in 1496, to Rome. He settled for a time in Bologna, where in 1494 and 1495 he executed several marble statuettes for the Arca (Shrine) di San Domenico in the Church of San Domenico.

In Rome he carved the first of his major works, the Bacchus (Florence, Bargello) and the St Peter's Pietà, which was completed by the turn of the century. It is highly finished and shows that he had already mastered anatomy and the disposition of drapery, but above all it shows that he had solved the problem of the representation of a full-grown man stretched out nearly horizontally on the lap of a woman, the whole being contained in a pyramidal shape.

The Pietà made his name and he returned to Florence in 1501 as a famous sculptor, remaining there until 1505. During these years he was extremely active, carving the gigantic David (1501-4, now in the Accademia), the Bruges Madonna (Bruges, Notre Dame), and beginning the series of the Twelve Apostles for the Cathedral which was commissioned in 1503 but never completed (the St Matthew now in the Accademia is the only one which was even blocked in). At about this time he painted the Doni Tondo of the Holy Family with St John the Baptist (Florence, Uffizi) and made the two marble tondi of the Madonna and Child (Florence, Bargello; London, Royal Academy).

After the completion of the David in 1504 he began to work on the cartoon of a huge fresco in the Council Hall of the new Florentine Republic, as a pendant to the one already commissioned from Leonardo da Vinci. Both remained unfinished and the grandiose project of employing the two greatest living artists on the decoration of the Town Hall of their native city came to nothing. Of Michelangelo's fresco, which was to represent the Battle of Cascina, an incident in the Pisan War, we now have a few studies by him and copies of a fragment of the whole full-scale cartoon which once existed (the best copy is the painting in Lord Leicester's Collection, Holkham, Norfolk). The cartoon, which is known as the Bathers, was for many years the resort of every young artist in Florence and, by its exclusive stress on the nude human body as a sufficient vehicle for the expression of alt emotions which the painter can depict, had an enormous influence on the subsequent development of Italian art - especially Mannerism - and therefore on European art as a whole. This influence is more readily detectable in his next major work, the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. In fact, however, the Battle of Cascina was left incomplete because the Signoria of Florence found it expedient to comply with a request from the masterful Pope Julius II, who was anxious to have a fitting tomb made in his lifetime.

The Julius Monument was, in Michelangelo's own view, the Tragedy of the Tomb. This was partly because Michelangelo and Julius had the same ardent temperament - they admired each other greatly - and very soon quarrelled, and partly because after the death of Julius in 1513, Michelangelo was under constant pressure from successive Popes to abandon his contractual obligations and work for them while equally under pressure from the heirs of Julius, who even went so far as to accuse him of embezzlement. The original project for a vast free-standing tomb with forty figures was substantially reduced by a second contract (1513), drawn up after Julius's death; under this contract the Moses, which is the major figure on the extant tomb, was prepared as a subsidiary figure. Two others, the Slaves in the Louvre, were made under this contract but were subsequently abandoned. The third contract (1516) was followed by a fourth (1532), and a fifth and final one in 1542, under the terms of which the present miserably mutilated version of the original conception was carried out by assistants, under Michelangelo's supervision, in S. Pietro in Vincoli (Julius's titular church) in 1545. Michelangelo was then 70 and had spent nearly forty years on the tomb.

Meanwhile, the original quarrel of 1506 with Julius was made up and Michelangelo executed a colossal bronze statue of the Pope as an admonition to the recently conquered Bolognese (who destroyed it as soon as they could, in 1511). In 1508, back in Rome, he began his most important work, the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican for Julius, who, as usual, was impatient to see it finished. Dissatisfied with the normal working methods and with the abilities of the assistants he had engaged, Michelangelo determined to execute the whole of this vast work virtually alone. Working under appalling difficulties (amusingly described in one of his own poems), most of the time leaning backwards and never able to get far enough away from the ceiling to be able to see what he was doing, he completed the first half (the part nearer to the door) in 1510. The whole enormous undertaking was completed in 1512, Michelangelo being by then so practised that he was able to execute the second half more rapidly and freely. It was at once recognized as a supreme work of art, even at the moment when Raphael was also at work in the Vatican Stanze. From then on Michelangelo was universally regarded as the greatest living artist, although he was then only 37 and this was in the lifetimes of Leonardo and Raphael (who was even younger). From this moment, too, dates the idea of the artist as in some sense a superhuman being, set apart from ordinary men, and for the first time it was possible to use the phrase 'il divino Michelangelo' without seeming merely blasphemous.

The Sistine Ceiling is a shallow barrel vault divided up by painted architecture into a series of alternating large and small panels which appear to be open to the sky. These are the Histories. Each of the smaller panels is surrounded by four figures of nude youths - the Slaves, or Ignudi - who are represented as seated on the architectural frame and who are not of the same order of reality as the figures in the Histories, since their system of perspective is different. Below them are the Prophets and Sibyls, and still lower, the figures of the Ancestors of Christ. The whole ceiling completes the chapel decoration by representing life on earth before the Law: on the walls is an earlier cycle of frescoes, painted in 1481-82, representing the Life of Moses (i.e. the Old Dispensation) and the Life of Christ (the New Dispensation). The Histories begin over the altar and work away from it (though they were painted in the reverse direction): the first scene represents God alone, in the Primal Act of Creation, and the story continues through the rest of the Creation to the Fall, the Flood, and the Drunkenness of Noah, representing the human soul at its furthest from God. The whole conception owes much to the Neoplatonic philosophy current in Michelangelo's youth in Florence, perhaps most in the idea of the Ignudi, perfect human beauty, on the level below the Divine story. Below them come the Old Testament Prophets and the Seers of the ancient world who foretold the coming of Christ; while the four corners have scenes from the Old Testament representing Salvation. The Prophet Jonah is above the altar, since his three days in the whale were held to prefigure the Resurrection. On the lowest parts - and very freely painted - are the human families who were the Ancestors of Christ. There can be no doubt that the splendour of the conception and the size of the task distracted Michelangelo from the Tomb, but he at once returned to it as soon as the ceiling was finished, from 1513 to 1516, when he returned to Florence to work for the Medici. (For details on the frescoes in the Sistine Chapel take a guided tour.)

His new master was Pope Leo X, the younger son of Lorenzo de Medici, who had known Michelangelo from boyhood; he now commissioned him to complete the façade of S. Lorenzo, the family church in Florence. Michelangelo wasted four years on this and it came to nothing. In 1520 he began planning the Medici Chapel, a funerary chapel in honour of four of the Medici - two of them by no means the most glorious of their family. The chapel is attached to S. Lorenzo. Leo X died in 1521 and it was not until after the accession of another Medici Pope, Clement VII, in 1523 that the project was resumed. Work began in earnest in 1524 and at the same time he was commissioned to design the Laurenziana Library in the cloister of the same church. Both these buildings are turning-points in architectural history, but the sculptural decoration of the chapel (an integral part of the architecture) was never completed, although the figures of Giuliano and Lorenzo de' Medici set over their tombs, eternally symbolizing the Active and the Contemplative Life, above the symbols of Time and Mortality - Day and Night, Dawn and Evening - are among his finest creations. The unfinished Madonna was meant to be the focal point of the chapel.

In 1527, the Medici were again expelled from Florence, and Michelangelo, who was politically a Republican in spite of his close ties with the Medici, took an active part in the 1527-29 war against the Medici up to the capitulation in 1530 (although in a moment of panic he had fled in 1529) and supervised Florentine fortifications. During the months of confusion and disorder in Florence, when he was proscribed for his participation in the struggle, it would appear that he was hidden by the Prior of S. Lorenzo. A number of drawings on the walls of a concealed crypt under the Medici Chapel have been attributed to him, and ascribed to this period. After the reinstatement of the Medici he was pardoned, and set to work once more on the Chapel which was to glorify them until, in 1534, he left Florence and settled in Rome for the thirty years remaining to him.

He was at once commissioned to paint his next great work, the Last Judgement on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel, which affords the strongest possible contrast with his own Ceiling. He began work on it in 1536. In the interval there had been the Sack of Rome and the Reformation, and the confident humanism and Christian Neoplatonism of the Ceiling had curdled into the personal pessimism and despondency of the Judgement. The very choice of subject is indicative of the new mood, as is the curious fact that the mouth of Hell gapes over the altar itself where, during services, stands a crucifix symbolizing Christ standing between Man and Doom. It was unveiled in 1541 and caused a sensation equalled only by his own work of thirty years earlier, and was the only work by him to be as much reviled as praised, and only narrowly to escape destruction, though it did not escape the mutilation of having many of the nude figures 'clothed' after his death. Most of the ideas of Mannerism are traceable implicitly or explicitly in the Judgement and, more than ever, it served to imprint the idea that the scope of painting is strictly limited to the exploitation of the nude, preferably in foreshortened - and therefore difficult - poses. Paul III, who had commissioned the Judgement, immediately commissioned two more frescoes for his own chapel, the Cappella Paolina; these were begun in 1542 and completed in 1550. They represent the Conversion of St Paul and the Crucifixion of St Peter.

Michelangelo was now 75 years old. Earlier, in 1538-39, plans were under way for the remodeling of the buildings surrounding the Campidoglio (Capitol) on the Capitoline Hill, the civic and political heart of the city of Rome. Although Michelangelo's program was not carried out until the late 1550s and not finished until the 17th century, he designed the Campidoglio around an oval shape, with the famous antique bronze equestrian statue of the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius in the center. For the Palazzo dei Conservatori he brought a new unity to the public building façade, at the same time that he preserved traditional Roman monumentality. However, since 1546 he had been increasingly active as an architect; in particular, he was Chief Architect to St Peter's and was doing more there than had been done for thirty years. This was the greatest architectural undertaking in Christendom, and Michelangelo did it, as he did all his late works, solely for the glory of God.

In his last years he made a number of drawings of the Crucifixion, wrote much of his finest poetry, and carved the Pietà (now in Florence Cathedral Museum) which was originally intended for his own tomb, as well as the nearly abstract Rondanini Pietà (Milan, Castello). This last work, in which the very forms of the Dead Christ actually merge with those of His Mother, is charged with an emotional intensity which contemporaries recognized as Michelangelo's 'terribilità'. He was working on it to within a few days of his death, in his 89th year, on 18 February 1564. There is a whole world of difference between it and the 'beautiful' Pietà in St Peter's, carved some sixty-five years earlier.

Unlike any previous artist, Michelangelo was the subject of two biographies in his own lifetime. The first of these was by Vasari, who concluded the first (1550) edition of his 'Vite' with the Life of one living artist, Michelangelo. In 1553 there appeared a 'Life of Michelangelo' by his pupil Ascanio Condivi (English translations 1903, 1976 and 1987); this is really almost an autobiography, promoted by Michelangelo to correct some errors of Vasari and to shift the emphasis in what Michelangelo regarded as a more desirable direction. Vasari, however, became more and more friendly with Michelangelo and was also his most devoted and articulate admirer, so that the very long Life which appears in Vasari's second edition (1568), after Michelangelo's death, gives us the most complete biography of any artist up to that time and is a trustworthy guide to the feelings of contemporaries about the man who can lay claim to be the greatest sculptor, painter and draughtsman that has ever lived, as well as one of the greatest architects and poets. He is the archetype of genius.

Pure fresco was his preferred painting technique; he despised oil-painting, though the now authenticated unfinished Entombment (London, National Gallery) is in oil over a tempera underpainting. The Doni Tondo is in tempera. In sculpture, his usual method was to outline his figure on the front of the block and, as he himself wrote, to 'liberate the figure imprisoned in the marble', by working steadily inwards, with perhaps a few more finished details. Occasionally he made drawings for parts of a figure, and a few small wax models survive as well as one large one, made for the guidance of assistants working on the Medici Chapel figures. The four abandoned Slaves intended for a later version of the Julius Tomb (Florence, Accademia) and the two marble tondi left unfinished in 1505 provide fine examples of his direct carving technique and his consistent use of various sizes of claw chisel. No modelli exist for any paintings or frescoes, and only one cartoon (London, British Museum), made to help Condivi, has survived.