Auguste Rodin

Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

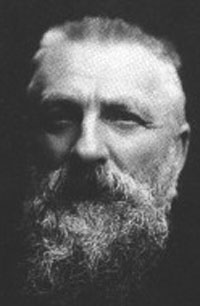

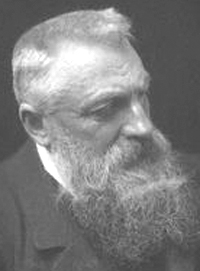

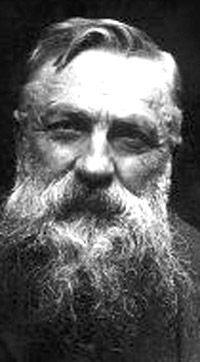

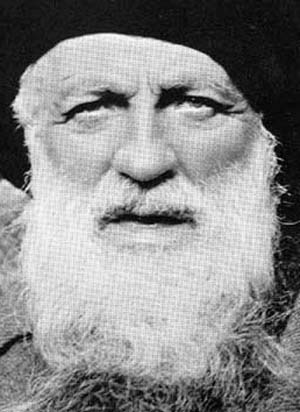

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

Auguste Rodin—Sculptor

(1840-1917) November 12, 1840, Paris, France, 12:00 PM, LMT. (Source: quotes from the biography Rodin by Victor Frisch) Died, November 17, 1917, Villa des Brillants in Meudon, France.

(Ascendant, Capricorn: Sun and Jupiter conjunct in Scorpio and conjunct the MC; Moon in Gemini; Venus conjunct Saturn in Sagittarius with Mercury also in Sagittarius; Mars in Virgo; Uranus in Pisces; Neptune in Aquarius; Pluto in Aries)

The fourth ray is abundantly present in the power and livingness of Rodin’s sculpture, but the seventh ray must also be considered. Capricorn, transmitting the seventh ray, is the Ascendant and is placed in Sagittarius (the sign of vision) conjunct to Venus (the planet of beauty)—so he was able to concretize his vision of beauty in form. (Carry this farther)

One of the world’s master sculptors, whose work influenced those who followed. His magnificent pieces include Age of Bronze, The Kiss, and The Thinker. Internationally famous by late life; received many honors.

Art is contemplation. It is the pleasure of the mind which searches into nature and which there divines the spirit of which nature herself is animated.

I choose a block of marble and chop off whatever I don't need.

Inside you there's an artist you don't know about. He's not interested in how things look different in moonlight.

Man's naked form belongs to no particular moment in history; it is eternal, and can be looked upon with joy by the people of all ages.

Nothing is a waste of time if you use the experience wisely.

The artist is the confidant of nature, flowers carry on dialogues with him through the graceful bending of their stems and the harmoniously tinted nuances of their blossoms. Every flower has a cordial word which nature directs towards him.

The artist must create a spark before he can make a fire and before art is born, the artist must be ready to be consumed by the fire of his own creation.

There are unknown forces in nature; when we give ourselves wholly to her, without reserve, she lends them to us; she shows us these forms, which our watching eyes do not see, which our intelligence does not understand or suspect.

To any artist, worthy of the name, all in nature is beautiful, because his eyes, fearlessly accepting all exterior truth, read there, as in an open book, all the inner truth.

(Venus, Saturn & Mercury in Sagittarius, trine Pluto in Aries.)To the artist there is never anything ugly in nature.

True artists are almost the only men who do their work for pleasure.

There is a continual exchange of ideas between all minds of a generation. Journalists, popular novelists, illustrators, and cartoonists adapt the truths discovered by the powerful intellects for the multitude. It is like a spiritual flood, like a gush that pours into multiple cascades until it forms the great moving sheet of water that stands for the mentality of a period.

(Sun in Scorpio conjunct Jupiter & MC. Gemini Moon.)Where shall we begin? There is no beginning. Start where you arrive. Stop before what entices you. And work! You will enter little by little into the entirety. Method will be born in proportion to your interest.

Nobody does good to man with impunity.

Nothing is a waste of time if you use the experience wisely.

The delicate droop of the petals standing out in relief, is like the eyelid of a child.

“There are unknown forces in nature; when we give ourselves wholly to her, without reserve, she lends them to us; she shows us these forms, which our watching eyes do not see, which our intelligence does not understand or suspect.”

“Man enjoys living on the edge of his dreams and neglects the real things of the world which are so beautiful. The ignorant and indifferent destroy beautiful things merely by looking at them. (Things that) remake the soul of him who understands them.”

“The modes of expression of men of genius differ as much as their souls, and it is impossible to say that in some among them, drawing and color are better or worse than in others.”

“Sculpture is the art of the hole and the lump.”

“I will have no other woman. ... Mlle Camille will become my wife.”

It is truly flesh! You would think it moulded by kisses and caresses! You almost expect, when you touch this body, to find it warm.

(Rodin talking about an antique marble copy of the Venus de' Medici)+ The sculptor represents the transition from one pose to another.. he indicates how insensibly the first glides into the second. In his work we still see a part of what was and we discover a part of what is to be.

+ It is the artist who is truthful and it is photography which lies, for in reality time does not stop, and if the artist succeeds in producing the impression of a movement which takes several moments for accomplishment, his work is certainly much less conventional than the scientific image, where time is abruptly suspended.

+ Recently I have taken to isolating limbs, the torso. Why am I blamed for it? Why is the head allowed and not portions of the body? Every part of the human figure is expressive.

+ Have pity, mean girl. I can't go on. I can't go another day without seeing you. Atrocious madness, it's the end, I won't be able to work anymore. Malevolent goddess, and yet I love you furiously. (Rodin writing to his lover Camille Claudel)

+ How painful it is to find that my figure can be of no help to my future.. how painful to see it rejected on account of a slanderous suspicion! (Rodin talking about a work he created that was so realistic, he was accused of creating the work from a mold).

What is commonly called ugliness in nature can in art become full of beauty.

There is nothing ugly in art except that which is without character, that is to say, that which offers no outer or inner truth.

If the artist only reproduces superficial features as photography does, if he copies the lineaments of a face exactly, without reference to character, he deserves no admiration. The resemblance which he ought to obtain is that of the soul.

Now colour... is the flower of fine modelling. These two qualities always accompany each other, and it is these qualities which give to every masterpiece of the sculptor the radiant appearance of living flesh.

What is this drawing? Not once in describing the shape of that mass did I shift my eyes from the model. Why? Because I wanted to be sure that nothing evaded my grasp of it... My objective is to test to what extent my hands already feel what my eyes see.

My drawings are the result of my sculpture.

I grant you that the artist does not see Nature as she appears to the vulgar, because his emotion reveals to him the hidden truths beneath appearances.

(Venus in Sagittarius)He who is discouraged after a failure is not a real artist.

People say I think too much about women, yet, after all what is there more important to think about?

Genius only comes to those who know how to use their eyes and their intelligence.

Work lovingly done is the secret of all order and all happiness.

The only principle in art is to copy what you see. Dealers in aesthetics to the contrary, every other method is fatal.

In front of the model I work with the same will to reproduce truth as if I were making a portrait. I do not correct nature, I incorporate myself into it; it directs me. I can only work with a model. The sight of human forms nourishes and comforts me.

(Capricorn Ascendant)All the best works of any artist must be bathed, so to speak, in mystery.

(Uranus in Pisces in 2nd house)I have unbounded admiration for the nude. I worship it like a god.

The body always expresses the spirit whose envelope it is. And for him who can see, the nude offers the richest meaning.

As paradoxical as it may seem a great sculptor is as much a colourist as the best painter, or rather the best engraver. He plays so skillfully with all the resources of relief, he blends so well the boldness of light with the modesty of shadow, that his sculptures please one, as much as the most charming etchings.

Where did I learn to understand sculpture? In the woods by looking at the trees, along roads by observing the formation of clouds, in the studio by studying the model, everywhere except in the schools.

A mediocre man copying nature will never produce a work of art, because he really looks without seeing, and though he may have noted each detail minutely, the result will be flat and without character... the artist on the contrary, sees; that is to say, his eye, grafted on his heart, reads deeply into the bosom of nature.

If we now seek the spiritual significance of the technique of Michelangelo we shall find that his sculpture expressed restless energy...

"The body is a temple that marches."

"I have always endeavored to express the inner feelings by the mobility of the muscles."

Auguste Rodin.Auguste Rodin (born François Auguste René Rodin; November 12, 1840 – November 17, 1917) was a French artist, most famous as a sculptor, but also a painter and printmaker. He was the preeminent French sculptor of his time, and remains one of the few sculptors with broad name recognition outside the visual arts community. Sculpturally, he possessed a unique ability to organize a complex, turbulent, deeply pocketed clay surface.

In late nineteenth-century Paris, Rodin played a pivotal role in redefining sculpture. The predominant figure sculpture tradition of the time required an almost formulaic approach, and most sculpture was either decorative or highly thematic. Rodin's most original work departed from traditional themes of mythology and allegory, modelled the human body with high realism, and celebrated individual character and physicality. Although Rodin is considered the progenitor of modern sculpture,[1] he did not set out to rebel against tradition. He was schooled traditionally in Paris's École des Beaux-Arts system, and desired academic recognition.[2]

Many of his most notable sculptures were roundly criticized during his lifetime, from the surprising realism of his first major figure, The Age of Bronze, to the unconventional memorials whose commissions he later sought. Rodin was sensitive to the controversy, but did not change his style, and successive works brought increasing favor from the government and the artistic community. By 1900, Rodin was a world-renowned artist. Wealthy private clients sought his work, and he kept company with a variety of high-profile intellectuals and artists. His sculpture suffered a decline in popularity after his death in 1917, but within a few decades his legacy solidified: he was the man who revitalized sculpture after centuries of stasis.

The Gates of Hell, Musée Rodin.Rodin was born in 1840 into a working-class family in Paris, the son of Marie Cheffer and Jean-Baptiste Rodin, a police department clerk. He was largely self-educated,[3] and began to draw at ten. From 14 to 17, he attended the Petite École, a school specializing in art and mathematics, where he studied drawing with de Boisbaudran and painting with Belloc. Rodin submitted a clay model of a companion to the Grand École in 1857 in an attempt to win entrance; he did not succeed, and two further applications were also denied.[4] Given that entrance requirements at the Grand Ecole were not particularly high,[5] the rejections were considerable setbacks. Rodin's inability to gain entrance may have been due to the judges' Neoclassical tastes, while Rodin had been schooled in light, 18th century sculpture. Leaving the Petite École in 1857, Rodin would earn a living as a craftsman and ornamenter for most of the next two decades, producing decorative objects and architectural embellishments.

Rodin's sister Maria, two years his senior, died of peritonitis in a convent in 1862. Her brother was anguished, and felt guilty because he had introduced Maria to an unfaithful suitor. Turning away from art, Rodin briefly joined a Christian order. Father Peter Julian Eymard recognized Rodin's talent, however, and encouraged him to continue with his sculpture. He returned to work as a decorator, while taking classes with animal sculptor Antoine-Louis Barye. The teacher's attention to detail—for example, in rendering the musculature of animals in motion—significantly influenced Rodin.[6]

In 1864, Rodin began to live with a young seamstress named Rose Beuret, with whom he would stay—with ranging commitment—for the rest of his life. The couple bore a son, Auguste-Eugène Beuret, in 1866. The year that Rodin met Beuret, he offered his first sculpture for exhibition, and entered the studio of Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse, a successful mass producer of objects d'art. Rodin worked as Carrier-Belleuse' chief assistant until 1870, designing roof decorations and staircase and doorway embellishments. With the arrival of the Franco-Prussian War, Rodin was called to serve in the National Guard, but his service was brief due to his near-sightedness.[7] Decorators' work had dwindled because of the war, yet Rodin needed to support his family. Carrier-Belleuse soon asked Rodin to join him in Belgium, where they would work on ornamentation for Brussels' stock exchange.

Rodin spent the next six years abroad. Though his relationship with Carrier-Belleuse deteriorated, he found other employment in Brussels, and his companion Rose soon joined him there. Having saved enough money to travel, Rodin visited Italy for two months in 1875, where he was drawn to the work of Donatello and Michelangelo.[8] Their work had a profound effect on his artistic direction.[9]: Rodin said, "It is [Michelangelo] who has freed me from academic sculpture."[10] Returning to Belgium, he began work on The Age of Bronze, a life-size male figure whose realism brought Rodin attention, but lead to accusations of sculptural cheating.

Artistic independence

Rose Beuret and Rodin returned to Paris in 1877, moving into a small flat on the Left Bank. Misfortune surrounded Rodin: his mother, who wanted to see her son marry, was dead, and his father was blind and senile, cared for by Rodin's sister-in-law, Aunt Thérèse. Rodin's eleven-year-old son Auguste, possibly mentally retarded or brain-damaged from a fall, was also in the ever-helpful Thérèse's care. Rodin had essentially abandoned his son for six years,[11] and would have a very limited relationship with him throughout their lives. Son and father now joined the couple in their flat, with Rose as caretaker. The charges of fakery surrounding The Age of Bronze continued. Rodin increasingly sought more soothing female companionship in Paris, and Rose stayed in the background.Rodin earned his living collaborating with more established sculptors on public commissions, primarily memorials and neo-baroque architectural pieces in the style of Carpeaux.[12] In competitions for commissions, he submitted models of Denis Diderot, Jean-Jacques Rosseau, and Lazare Carnot, all to no avail. He worked on his own time on studies leading to the creation of his next important work, St. John the Baptist Preaching.

In 1880, Carrier-Belleuse—now art director of the Sèvres national porcelain factory—offered Rodin a part-time position as a designer. The offer was in part a gesture of reconciliation, and Rodin accepted. That part of Rodin that appreciated 18th-century tastes was aroused, and he immersed himself in designs for vases and table ornaments that gave the factory renown across Europe.[13] The artistic community appreciated his work in this vein, and Rodin was invited to society gatherings by such friends as writer Léon Cladel. French stateman Leon Gambetta expressed a desire to meet Rodin, and at this salon the sculptor impressed him. In turn, Gambetta spoke of Rodin to several government ministers, likely including Edmund Turquet, the Undersecretary of the Ministry of Fine Arts.[14]

Rodin's relationship with Turquet was rewarding: through him, he won the 1880 commission to create a portal for a planned museum of decorative arts. Rodin dedicated much of the next four decades to his elaborate Gates of Hell, an unfinished portal for a museum that was never built. Many of the portal's figures became sculptures in themselves, including The Thinker and The Kiss. With the commission came a free, sizeable studio, granting Rodin a new level of artistic freedom. Soon, he stopped working at the porcelain factory; his income came from private commissions.

Rodin in 1893.

Camille Claudel (1864–1943).In 1883, Rodin agreed to supervise a sculpture course for Alfred Boucher during his absence, where he met the 18-year-old Camille Claudel. The two formed a passionate but stormy relationship, and influenced each other artistically. Claudel inspired Rodin as a model for many of his figures, and she was a talented sculptor, assisting him on commissions.Although busy with The Gates of Hell, Rodin won other commissions. He pursued an opportunity to create a monument for the French town of Calais, to depict an important moment in the town's history. For a monument to French author Honoré de Balzac, Rodin was chosen in 1891. His execution of both sculptures clashed with traditional tastes, and met with varying degrees of disapproval from the organizations that sponsored the commissions. Still, Rodin was gaining support from diverse sources that continued his path toward fame.

In 1889, the Paris Salon invited Rodin to be a judge on its artistic jury. Though Rodin's career was on the rise, Claudel and Beuret were becoming increasingly impatient with Rodin's "double life". Claudel and Rodin shared an atelier at a small old castle, but Rodin refused to relinquish his ties to Beuret, his loyal companion during the lean years, and mother of his son. During one absence, Rodin wrote to her, "I think of how much you must have loved me to put up with my caprices…I remain, in all tenderness, your Rodin."[15] He never fulfilled a contract with Claudel to give up all contact with other women and marry her. The couple parted in 1898,[16] and Claudel's mental health deteriorated.

Character

Known for his love affairs and his interest in the sensual, Rodin was a short, stocky, and bearded man, sometimes referred to as a "brute".[17] Very devoted to his craft, he worked constantly, but not feverishly. Though he has been stereotyped as temperamental and loquacious— especially in his later years—he has also been described as possessing a silent strength,[18] and during his first appearances at Parisian salons, he seemed shy.[19] Decades after the charges of surmoulage early in his career, he was still wary of garnering such criticism—he ensured that the sizes or designs of his figures made it obvious that his creations were entirely original.Art

In 1864, Rodin submitted his first sculpture for exhibition, The Man with the Broken Nose, to the Paris Salon. The subject was an elderly neighbourhood street porter. The unconventional bronze piece was not a traditional bust, but instead the head was "broken off" at the neck, the nose was flattened and crooked, and the back of the head was absent, having fallen off the clay model in an accident. The work emphasized texture and the emotional state of the subject; it illustrated the "unfinishedness" that would characterize many of Rodin's later sculptures.[20] The Salon rejected the piece.Early figures: the inspiration of Italy

The Age of Bronze, 1877.In Brussels, Rodin created his first full-scale work, The Age of Bronze, having returned from Italy. Modelled by a Belgian soldier, the figure drew inspiration from Michelangelo's Dying Slave, which Rodin had observed at the Louvre. Attempting to combine Michelangelo's mastery of the human form with his own sense of human nature, Rodin studied his model from all angles, at rest and in motion; he mounted a ladder for additional perspective, and made clay models, which he studied by candlelight. The result was a life-size, well-proportioned nude figure, posed unconventionally with his right hand atop his head, and his left arm held out at his side, forearm parallel to the body.In 1877, the work debuted in Brussels and then was shown at the Paris Salon. The statue's apparent lack of a theme was troubling to critics—it did not commemorate mythology nor a noble historical event—and it is not clear whether Rodin intended a theme.[21] He first titled the work The Vanquished, in which form the left hand held a spear, but he removed the spear because it obstructed the torso from certain angles. After two more intermediary titles, Rodin settled on The Age of Bronze, suggesting the Bronze Age, and in Rodin's words, "man arising from nature".[22] Later, however, Rodin said that he had in mind "just a simple piece of sculpture without reference to subject".[23]

Its mastery of form, light, and shadow made the work look so realistic that Rodin was accused of surmoulage—having taken a cast from a living model.[8] Rodin vigorously denied the charges, writing to newspapers and having photographs taken of the model to prove how the sculpture differed. He demanded an inquiry and was eventually exonerated by a committee of sculptors. Leaving aside the false charges, the piece polarized critics. It had barely won acceptance for display at the Paris Salon, and criticism likened it to "a statue of a sleepwalker" and called it "an astonishingly accurate copy of a low type".[24] Others rallied to defend the piece and Rodin's integrity. The government minister Turquet admired the piece, and The Age of Bronze was purchased by the state for 2,200 francs—what it had cost Rodin to have it cast in bronze.[25]

A second male nude, St. John the Baptist Preaching, was completed in 1878. Rodin sought to avoid another charge of surmoulage by making the statue larger than life: St. John stands almost 6'7''. While the The Age of Bronze is statically posed, St. John gestures and seems to move toward the viewer. The effect of walking is achieved despite the figure having both feet firmly on the ground—a physical impossibility, and a technical achievement that was lost on most contemporary critics.[26] Rodin chose this contradictory position to, in his words, "display simultaneously…views of an object which in fact can be seen only successively".[27] Despite the title, St. John the Baptist Preaching did not have an obviously religious theme. The model, an Italian peasant who presented himself at Rodin's studio, possessed an idiosyncratic sense of movement that Rodin felt compelled to capture. Rodin thought of John the Baptist, and carried that association into the title of the work.[28] In 1880, Rodin submitted the sculpture to the Paris Salon. Critics were still mostly dismissive of the work, but the piece finished third in the Salon's sculpture category.[29]

Regardless of the immediate receptions of St. John and The Age of Bronze, Rodin had achieved a new degree of fame. Students sought him at his studio, praising his work and scorning the charges of surmoulage. The artistic community knew his name.

Hell-spawn

The Thinker, Sakip Sabanci Museum, Istanbul.A commission to create a portal for the planned Museum of Decorative Arts was awarded to Rodin in 1880.[12] Although the museum was never built, Rodin worked throughout his life on elements of this monumental sculptural group, The Gates of Hell, depicting scenes from Dante's Inferno in high relief. Many of his best-known sculptures started as designs of figures for this monumental composition,[6] such as The Thinker (Le Penseur), The Three Shades (Les Trois Ombres), and The Kiss (Le Baiser), and only later presented as separate and independent works.The Thinker (Le Penseur, originally titled The Poet, after Dante) was to become one of the most well-known sculptures in the world.[30][31] The original was a 27.5 inch-high bronze piece created between 1879 and 1889, designed for the Gates' lintel, from which the figure would gaze down upon Hell. While The Thinker most obviously characterizes Dante, aspects of the Biblical Adam, the mythological Prometheus,[12] and Rodin himself have been ascribed to him.[30][32] Other observers stress the figure's rough physicality and emotional tension, and suggest that The Thinker's renowned pensiveness is not intellectual.[33]

Other well-known works derived from The Gates are the Ugolino group, Fugitive Love, The Falling Man, The Sirens, Fallen Caryatid Carrying her Stone, Damned Women, The Standing Fauness, The Kneeling Fauness, The Martyr, She Who Once Was the Beautiful Helmetmaker's Wife, Glaucus, and Polyphem.

The Burghers of Calais

The Burghers of Calais in Victoria Tower Gardens, London, England.The town of Calais had contemplated an historical monument for decades when Rodin learned of the project. He pursued the commission, interested in the medieval motif and patriotic theme. The mayor of Calais was tempted to hire Rodin on the spot upon visiting his studio, and soon the memorial was approved, with Rodin as its architect. It would commemorate the six townspeople of Calais who offered their lives to save their fellow citizens. During the Hundred Years' War, the army of King Edward III besieged Calais, and Edward asked for six citizens to sacrifice themselves and deliver to him the keys to the city, or the entire town would be pillaged. The Burghers of Calais depicts the men as they are leaving for the king's camp, carrying keys to the town's gates and citadel.Rodin began the project in 1884, inspired by the chronicles of the siege by Jean Froissart.[34] Though the town envisioned an allegorical, heroic piece centred on Eustache de Saint-Pierre, the eldest of the six men, Rodin conceived the sculpture as a study in the varied and complex emotions under which all six men were laboring. One year into the commission, the Calais committee was not impressed with Rodin's progress. Rodin indicated his willingness to end the project rather than change his design to meet the committee's conservative expectations, but Calais said to continue.

In 1889, The Burghers of Calais was first displayed to general acclaim. It is a bronze sculpture weighing two tons, and its figures are 2 metres tall.[34] The six men portrayed do not display a united, heroic front;[35] rather, each is isolated from his brothers, individually deliberating and struggling with his expected fate. Rodin soon proposed that the monument's high pedestal be eliminated, wanting to move the sculpture to ground level so that viewers could "penetrate to the heart of the subject".[36] At ground level, the figures' positions lead the viewer around the work, and subtly suggest their common movement forward.[37] The committee was incensed by the non-traditional proposal, but Rodin would not yield. In 1895, Calais succeeded in having Burghers displayed its way: the work was placed in front of a public garden on a high platform, surrounded by a cast-iron railing. Rodin had wanted it located near the town hall, where it would engage the public. Only after damage during the First World War, subsequent storage, and Rodin's death was the sculpture displayed as he had intended. It is one of Rodin's most well-known and acclaimed works.[34]

Commissions and controversy

Monument to Balzac.The Société des Gens des Lettres, a Parisian organization of writers, planned a monument to French novelist Honoré de Balzac immediately after his death in 1850. The society commissioned Rodin to create the memorial in 1891, and Rodin spent years developing the concept for his sculpture. Challenged in finding an appropriate representation of Balzac given his rotund physique, Rodin produced many studies: portraits, full-length figures in the nude, wearing a frock coat, or in a robe—a replica of which Rodin had tailored to contemplate upon. The realized version displayed Balzac cloaked in the ample drapery, looking forcefully into the distance, with deeply gouged features. Rodin's intent had been to show Balzac at the moment of conceiving a work[38]—to express courage, labor, and struggle.[39]When Balzac was exhibited in 1898, the negative reaction was not surprising.[30] The Société rejected the work, and the press ran parodies. Criticizing the work, Morey (1918) reflected, "there may come a time, and doubtless will come a time, when it will not seem outre to represent a great novelist as a huge comic mask crowning a bathrobe, but even at the present day this statue impresses one as slang."[6] A contemporary critic, indeed, indicates that Balzac is considered one of Rodin's masterpieces.[40] The monument had its supporters in Rodin's day; a manifesto defending him was signed by Monet, Debussy, and future Premier Georges Clemenceau, among many others.[41]

Rather than try to convince skeptics of the merit of the monument, Rodin repaid the Société his commission and moved the figure to his garden. After this experience, Rodin did not complete another public commission.Only in 1939 was Monument to Balzac cast in bronze.

Commissioned to create a monument to French writer Victor Hugo in 1889, Rodin dealt extensively with the subject of artist and muse. Like many of Rodin's public commissions, Monument to Victor Hugo met with resistance because it did not fit conventional expectations. Commenting on Rodin's monument to Victor Hugo, The Times in 1909 expressed that "there is some show of reason in the complaint that [Rodin's] conceptions are sometimes unsuited to his medium, and that in such cases they overstrain his vast technical powers".[42] The 1897 plaster model was not cast in bronze until 1964.

Other works

The popularity of Rodin's most famous sculptures tends to obscure his total creative output. A prolific artist, he created thousands of busts, figures, and sculptural fragments over more than five decades. He painted in oils (especially in his thirties) and in watercolors. The Musée Rodin holds 7,000 of his drawings and prints, in chalk, charcoal, and 13 very vigorous drypoints.[43][44] He also produced a single lithograph.Portraiture was an important component of Rodin's oeuvre, helping him to win acceptance and financial independence.[45] His first sculpture was a bust of his father in 1860, and he produced at least 56 portraits between 1877 and his death in 1917.[46] Early subjects included fellow sculptor Jules Dalou (1883) and companion Camille Claudel (1884). Later, with his reputation established, Rodin made busts of prominent contemporaries such as English politician George Wyndham (1905), Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw (1906), Austrian composer Gustav Mahler (1909), and French statesman Georges Clemenceau (1911).

Aesthetic

A famous "fragment": The Walking Man.Rodin was a naturalist, less concerned with monumental expression than with character and emotion.[47] Departing with centuries of tradition, he turned away from the abstraction and idealism of the Greeks, and the decorative beauty of the Baroque and neo-Baroque movements. His sculpture emphasized the individual and the concreteness of flesh, and suggested emotion through detailed, textured surfaces, and the interplay of light and shadow. To a greater degree than his contemporaries, Rodin believed that an individual's character was revealed by his physical features.[48]Rodin's talent for surface modeling allowed him to let every part of the body speak for the whole. The male's passion in The Kiss is suggested by the grip of his toes on the rock, the rigidness of his back, and the differentiation of his hands.[6] Speaking of The Thinker, Rodin illuminated his aesthetic: "What makes my Thinker think is that he thinks not only with his brain, with his knitted brow, his distended nostrils and compressed lips, but with every muscle of his arms, back, and legs, with his clenched fist and gripping toes."[49]

To Rodin, sculptural fragments were autonomous works, and he considered them to portray the essence of his artistic statement. His fragments—perhaps lacking arms, legs, or a head—took sculpture further from its traditional role of portraying likenesses, and into a realm where forms existed for their own sake.[50] Notable examples are The Walking Man, Meditation without Arms, and Iris, Messenger of the Gods.

Rodin saw suffering and conflict as hallmarks of modern art. "Nothing, really, is more moving than the maddened beast, dying from unfulfilled desire and asking in vain for grace to quell its passion."[32] Charles Baudelaire echoed those themes, and was among Rodin's favorite poets. Rodin enjoyed music, especially the opera composer Gluck, and wrote a book about French cathedrals. He owned a work by the as-yet-unrecognized Van Gogh, and admired the forgotten El Greco.[17]

Method

A plaster of The Age of Bronze.Instead of copying traditional academic postures, Rodin preferred to work with amateur models, street performers, acrobats, strong men and dancers. In the atelier, his models moved about and took positions without manipulation.[6] The sculptor made quick sketches in clay that were later fine-tuned, cast in plaster, and forged into bronze or carved in marble. Rodin was fascinated by dance and spontaneous movement; his John the Baptist shows a walking preacher, displaying two phases of the same stride simultaneously. As France's best-known sculptor, he had a large staff of pupils, craftsmen, and stone cutters working for him, including the Czech sculptors Josef Maratka and Joseph Kratina. Through his method of marcottage (layering), he used the same sculptural elements time and time again, under different names and in different combinations. Disliking the formality of pedestals, Rodin placed many of his subjects around rough rock to emphasize their immediacy and provide contrast.[51]Later years

A portrait of Rodin by his friend Alphonse Legros.By 1900, Rodin's artistic reputation was entrenched. Gaining exposure from a pavilion of his artwork set up near the 1900 World's Fair (Exposition Universelie) in Paris, he received requests to make busts of prominent people internationally,[30] while his assistants at the atelier produced duplicates of his works. His income from portrait commissions alone totalled probably 200,000 francs a year.[52] As Rodin's fame grew, he attracted many followers, including the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke, and authors Octave Mirbeau, Joris-Karl Huysmans, and Oscar Wilde.[35] Rilke stayed with Rodin in 1905 and 1906, and did administrative work for him; he would later write a laudatory monograph on the sculptor. Rodin and Beuret's modest country estate in Meudon, purchased in 1897, became a regular host to such visitors as King Edward, dancer Isadora Duncan, and harpsichordist Wanda Landowska. Rodin moved to the city in 1908, renting the main floor of the Hôtel Biron, an 18th century townhouse. He left Beuret in Meudon, and began an affair with the American-born Duchesse de Choiseul.[53]After the turn of the century, Rodin was a regular visitor to Great Britain, where he developed a loyal following by the beginning of the First World War. He first visited England in 1881, where his friend, the artist Alphonse Legros, had introduced him to the poet William Ernest Henley. Given Henley's personal connections and enthusiasm for Rodin's art, he was most responsible for Rodin's reception in Britain.[54] Through Henley, Rodin met Robert Louis Stevenson and Robert Browning, in whom he found further support.[55] Encouraged by the enthusiasm of British artists, students, and high society for his art, Rodin donated a significant selection of his works to the nation in 1914.

During his later creative years, Rodin's work turned increasingly toward the female form, and themes of more overt masculinity and femininity.[30] He concentrated on small dance studies, and produced numerous erotic drawings, sketched in a loose way, without taking his pencil from the paper or his eyes from the model. Rodin met American dancer Isadora Duncan in 1900, attempted to seduce her,[56] and the next year sketched studies of her and her students. In July 1906, Rodin was also enchanted by dancers from the Royal Ballet of Cambodia, and produced some of his most famous drawings from the experience.[57]

Fifty-three years into their relationship, Rodin married Rose Beuret. The wedding was January 29, 1917, and Beuret died two weeks later, on February 16.[58] Rodin was ill that year; in January, he suffered weakness from influenza,[59] and on November 16 his physician announced that "[c]ongestion of the lungs has caused great weakness. The patient's condition is grave."[58] Rodin died the following day, age 77, at his villa in Meudon, Île-de-France, on the outskirts of Paris.[4] A cast of The Thinker was placed next to his tomb in Meudon.

Legacy

Rodin willed to the state his studio and the right to make casts from his plasters. Because he encouraged the reproduction of his work, Rodin's sculptures are represented in many collections. The Musée Rodin in Paris, founded in 1919, holds the largest Rodin collection. The relative ease of making reproductions has also encouraged many forgeries: a survey of expert opinion placed Rodin in the top ten most-faked artists.[60] To deal with unauthorized reproductions, the Musée in 1956 set twelve casts as the maximum number that could be made from Rodin's plasters and still be considered his work. (As a result of this limit, The Burghers of Calais, for example, is found in 14 cities.)[34] Art critics concerned about authenticity have argued that taking a cast does not equal reproducing a Rodin sculpture—especially given the importance of surface treatment in Rodin's work.[61] In the market for sculpture, plagued by fakes, being able to prove the authenticity of a piece by its provenance increases its value significantly. A Rodin work with a verified history sold for US$4.8 million in 1999.[62]During his lifetime, Rodin was compared to Michelangelo,[32] and was widely recognized as the greatest artist of the era.[63] In the three decades following his death, his popularity waned with changing aesthetic values.[63] Since the 1950s, Rodin's reputation has re-ascended;[17] he is recognized as the most important sculptor of the modern era, and has been the subject of much scholarly work.[63][64] The sense of incompletion offered by some of his sculpture, such as The Walking Man, influenced the increasingly abstract sculptural forms of the twentieth century.[65] Though highly honoured for his artistic accomplishments, Rodin did not spawn a significant, lasting school of followers. His notable students included Antoine Bourdelle, Charles Despiau, the American Malvina Hoffman, and his mistress Camille Claudel, whose sculpture received high praise in France. The French order Légion d'honneur made him a Commander, and he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Oxford.

Rodin restored an ancient role of sculpture—to capture the physical and intellectual force of the human subject[64]—and he freed sculpture from the repetition of traditional patterns, providing the foundation for greater experimentation in the twentieth century. His popularity is ascribed to his emotion-laden representations of ordinary men and women—to his ability to find the beauty and pathos in the human animal. His most popular works, such as The Kiss and The Thinker, are widely used outside the fine arts as symbols of human emotion and character.[66]

Childhood 1840-1858

Born to modest means on November 12, 1840, François-Auguste-René Rodin was the second child of Jean-Baptiste Rodin and Marie Cheffer. He was somewhat shy and very nearsighted, which proved a hindrance in his early academic work. He took a serious interest in drawing and had his first drawing lesson when he was ten years old. His father tried to help him academically by sending him to his uncle's boarding school in Beauvais in 1851. He remained there for three years, but still had difficulty reading and writing, and the time was soon approaching for him to learn a trade.

Devoting himself to drawing early on, Rodin enrolled at the École Impériale de Dessin, a government school for craft and design (also called the "Petite École" or "Small School" to distinguish itself from the more prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, or "School of Fine Arts".) He kept himself very busy, attending classes at La Petite École, visiting museums to study antique sculpture, and attending the Gobelins tapestry manufactory, where he also studied drawing. During these early years he also discovered clay and found himself to be a very capable and promising sculptor. Although he was awarded two prizes for drawing and modeling at the age of seventeen, Rodin was unable to gain admittance to the prestigious and conservative École des Beaux-Arts, which rejected him three times.

Early Struggles 1858-1870

To help support his family Rodin began working commercially in the decorative arts in 1858. Paris was in a time of transformation, many statues and other ornamental sculptures were being erected throughout the city in courtyards, squares and in front of public buildings. Numerous workshops throughout Paris were hiring artists to work on these public projects. Rodin endured several years of laboring for others by day and trying to fulfill his personal artistic aspirations by night.Grief stricken by the unexpected death of his sister in 1862, Rodin briefly joined a Catholic order. Father Eymard, founder of the Order of the Holy Sacrament, quickly detected that the monastic life was not Rodin's true calling. He encouraged Rodin to draw and sculpt in order to revive him from his saddened mental state. Father Eymard was successful and Rodin left the monastery to pursue his dreams of being a sculptor.

Continuing to support himself by working for decorative sculptors, Rodin was able to afford to rent his first studio: a small, cold, and drafty stable. In the fall of 1863, he began working on a portrait bust that he intended to submit as his debut sculpture to the Paris Salon. The Salon was the official exhibition held annually where artists could display their work to the public. The atmosphere was very competitive, as each artist sought buyers for their work. The official prizes awarded greatly influenced what was sold. The Salon could make or break an artist's reputation.

Rodin working on Father Eymard's bust, 1863

Photograph by Charles Aubrey

For the first time, Rodin hired a model to sit for him. The model was not a professional, but rather a neighborhood handyman named Bibi. Rodin was very drawn to his features and wanted to depict him as he was– broken nose and all. The Man with the Broken Nose became The Mask of the Man with the Broken Nose when the cold conditions of Rodin's studio caused the back of the head to freeze and break off. Rodin, favoring the element of chance, wanted to exhibit the portrait bust as it was. He continued to work on it for over a year before submitting it to the Salon. Much to his disappointment, the Salon rejected the work twice during 1864 and 1865. Rodin considered the portrait to be his earliest major work and described it as the first exceptional piece of modeling he ever did.During this time Rodin also met his lifetime companion, Rose Beuret, while working on a decorative commission. She became his model and mistress and remained completely devoted to him throughout her life. In 1866 she gave birth to their son, although Rodin did not legally acknowledge paternity.

Inspiration and Controversy 1870-1880

In 1870 the Franco-Prussian War broke out. Thirty-year old Rodin was drafted into the National Guard, but was soon discharged due to his nearsightedness. Finding himself without work, Rodin accepted a job with Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse, a fashionable commercial sculptor whom Rodin had worked with off-and-on for several years. Carrier-Belleuse had been commissioned to decorate the new stock exchange in the Belgian capital of Brussels. Rodin decided to go to Brussels alone, leaving Rose and their son behind in Paris. His stay in Belgium lasted six years and would prove to be a creative and inspirational time for him. In Brussels Rodin held his first exhibition, marking his debut as an independent sculptor.After an inspiring trip to Italy in 1875, Rodin began work on a large-scale statue intended for submission to the Paris Salon. Auguste Neyt, a Belgian soldier, was his model. The life-size male nude, first titled The Vanquished, showed influences of classical sculpture but was modeled in a more naturalistic way, without the exaggerated musculature that Greek and Roman sculptors often used. He first presented The Vanquished in Brussels, where critics were suspicious of the statue's incredible realism and accused Rodin of making a cast from the live model, a technique that a true sculptor would never use. Rodin tried to defend himself against the accusations, but to no avail. He returned to Paris but the rumors followed him as he submitted the nude, now titled The Age of Bronze, to the Paris Salon of 1877. It was praised for its beauty, but Rodin was again forced to defend himself against allegations of casting from a live model.

Age of Bronze, 1876Upon returning to Paris, Rodin supplemented his income by working for the Sèvres porcelain factory again with Carrier-Belleuse. The income was small so he accepted additional work wherever he could find it. During this time Rodin created one of his most powerful figures, Saint John the Baptist, which would be exhibited with The Age of Bronze in 1880. Partly to exonerate himself of the previous allegations, Rodin made this figure larger than life-size. He created a stir among critics, however, for his uncommon portrayal of the saint. His figure did not depend on Saint John's more common attributes– a hair shirt, leather belt, or a cross and scroll– but presented an unidealized nude figure which his contemporaries found improper, ugly, and shocking.

Middle Years

The Gates of Hell, 1880-c. 1900

Monumental Projects

and Growing Notoriety 1880-1900Despite the criticism and controversy of the early part of his career, Rodin was commissioned by the French Ministry of Fine Arts to design his first large-scale public project in 1880. The proposition was to create an entrance portal for a museum of decorative arts to be built in Paris. Rodin's main source of inspiration for the doorway, soon to be called The Gates of Hell, was The Divine Comedy by twelfth-century epic poet Dante Aligheri. The Inferno, one of the three parts of The Divine Comedy, was a common reference in French art and literature during this time. An avid reader of Dante, Rodin borrowed imagery directly from The Inferno in addition to creating his own unique visual representations. He wanted to emulate Dante's journey through the underworld as a three-dimensional single piece that would incorporate many characters and scenes. He also drew inspiration from Charles Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil), a controversial book of verse from 1857.

Several of his most famous independent sculptures, such as The Thinker, The Kiss and The Three Shades, were derived from smaller reliefs contained within The Gates of Hell. Beginning in the 1880's, Rodin exhibited many of these figures independently as freestanding sculptures. By the end of the 1880's it was clear that the museum of decorative arts would never be built, but Rodin continued to work on the project periodically for the duration of his life.

During the 1880s, while working on The Gates, Rodin was gaining notoriety. His work became more and more sought after, especially among fashionable society people. He modeled many portrait busts, often not as paid commissions but as gestures of thanks or friendship. As his reputation grew so did the activity in his studio. Rodin had several people assisting him, each having their own particular job. There were assistants who created plaster casts of the original clay models, a "pointer" who would ready marble blocks to be carved, a bronze caster, and a patinater who finished the outer surface of the completed bronze sculpture.

It was also during this period that Rodin met nineteen-year-old Camille Claudel while filling in for his friend who taught a sculpture class to a group of young women. Rodin soon became captivated by Camille, who had noticeable talent and an intense desire to succeed as a sculptor. While Rodin always retained his feelings for Rose Beuret, he and Camille shared more similar interests and passions. Before long she became his student, model, collaborator, and mistress. The two held a great admiration for each other that was notably evident in both of their works. Rodin created many sculptures with Camille serving as his inspiration. He made many portraits of her, in addition to creating numerous sculptures of loving couples in passionate embraces, such as one of his most famous works, The Kiss. Although they were very much in love, Rodin refused to leave his long-time companion Rose Beuret and he and Camille severed their ties by 1898.

The Kiss, c. 1881-82In 1884 Rodin took on another monumental project, this time for the city of Calais, France. The mayor of Calais commissioned a monument to be erected in honor of a local hero, Eustache de Saint-Pierre. This hero was part of a dramatic event that occurred in 1347, during the Hundred Years War. Six leading citizens of Calais volunteered themselves as hostages to the English King Edward III in exchange for his lifting an eleven-month siege on their city. Eustache de Saint-Pierre was the first of six burghers to surrender. The king ordered them to relinquish the keys to the city and to prepare themselves for execution. The brave citizens walked towards the king's camp, thinking that they were taking their last steps, but in the end their lives were spared.

Rodin was greatly moved by the power of the story and offered to depict all six men for a modest sum. He began by studying the history surrounding the event as well as other artistic depictions of the burghers. He decided to show all six men taking their first steps toward the camp of Edward III. Rodin's originality won him the commission for the monument and by 1885 he was completing a second maquette for the final approval of the Municipal Council.

Two years before its completion, the commissioners of the monument disbanded. Rodin, however, finished the Burghers of Calais in 1888 and exhibited it to the public in 1889 at a joint exhibition in Paris with Impressionist painter Claude Monet. The monument was not erected in Calais until 1895 and even then it was not placed to Rodin's specifications.

Balzac in Dominican Robe, 1891-92In the late 1880's Rodin continued to receive commissions for public monuments including a monument to painter Claude Lorrain and another monument to French novelist Victor Hugo. In 1891 Rodin received a commission by the Société des Gens de Lettres (the Society of Men of Letters) to create a monument to their founder, French writer Honoré de Balzac. Since Balzac had been dead for forty years, Rodin faced the challenge of having to render his likeness from photographs. He researched the writer extensively, going so far as to order a suit from Balzac's tailor to visualize his size and girth.

Rodin worked on the Monument to Balzac for seven years. He completed at least fifty studies, some based on Balzac's actual appearance and others more subjective and abstract. Most of the studies were of Balzac's head, as Rodin felt it more important to emphasize the heads of people of such high intellect. He finished the monument in 1898 and presented the final nine-foot plaster model to the public. It was met with outrage, disbelief, and ridicule, and as a result the literary society refused to accept it. Deeply hurt by the criticism, Rodin removed the sculpture to his studio at Meudon, outside of Paris, and refused to allow it to be cast during his lifetime.

Later YearsThe Pinnacle of Success 1900-1917

By 1900 Rodin had achieved the pinnacle of success. European nobility paid him tribute and an entire pavilion was devoted to his work at the Paris World Exposition. One hundred sixty-eight works were displayed in bronze, marble, and plaster. Drawings and photos also adorned the walls and lectures were given explaining Rodin's techniques. People came from all over the world to visit the Exhibition, which made Rodin a success on an international scale. His work became immensely popular as requests for exhibitions began to surface from Montreal to Tokyo.

Monument to Victor Hugo,

large model incomplete 1897

definitive model completed shortly after 1900 Rodin's incredible popularity did not slow his production. He revisited old figures, modeled portrait busts of well known people, and completed several long term projects, such as the Monument to Victor Hugo and a large scale version of The Thinker. During these later years he also took a great interest in the study of dancers as part of his desire to capture natural, spontaneous movement. With commissions continuing to flood in, it has been speculated that Rodin had as many as fifty assistants working for him during this busy period.In 1908 Rodin moved to the Hôtel Biron outside Paris. The Hôtel Biron had previously been home to a religious community before the separation of church and state. The rent was very low and Rodin was able to occupy much of the ground floor. Several famous or soon to be famous tenants also lived there such as writer Jean Cocteau, painter Henri Matisse, and dancer Isadora Duncan.

Rodin's Funeral in Meudon,

November 24, 1917

In 1912, the state scheduled the Hôtel Biron for demolition and ordered the tenants to vacate. After persuading state officials, Rodin was allowed to stay. As an exchange, Rodin offered to bequeath his entire estate to the French government if he could reside at the Hôtel Biron for the remainder of his days and if they would convert the Hotel to a musuem for his work after he died. After much debate the state finally accepted the terms and he was allowed to live and work there for the remainder of his life. The final seal of the agreement, however, was not actually settled until one year before his death.During his last year Rodin married his lifetime companion Rose Beuret on January 29, 1917. Rose died three weeks later and Rodin followed shortly, passing away on November 17, 1917. Friends and dignitaries came to Rodin's funeral to see him laid to rest beside Rose at Meudon with The Thinker at the base of his tomb.