Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological

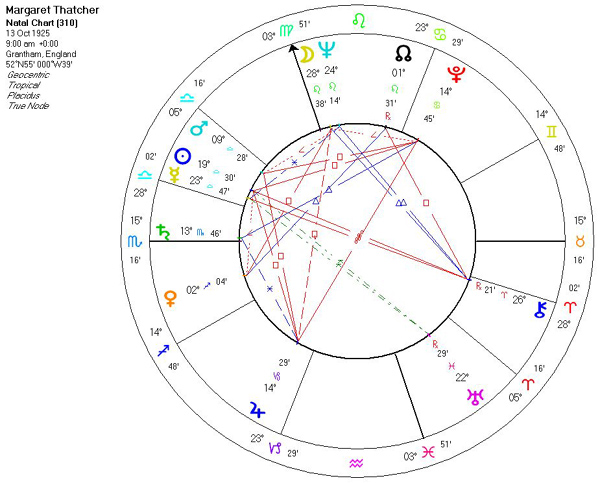

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

A world without nuclear weapons would be less stable and more dangerous for all of us.

(Saturn rising in Scorpio; Libra Mercury, Sun, Mars in the 11th)Any woman who understands the problems of running a home will be nearer to understanding the problems of running a country.

(Uranus in the fourth)Being powerful is like being a lady. If you have to tell people you are, you aren't.

(Jupiter in Capricorn)Being prime minister is a lonely job... you cannot lead from the crowd.

(Saturn rising)Democratic nations must try to find ways to starve the terrorist and the hijacker of the oxygen of publicity on which they depend.

(Moon Neptune in the 9th)Disciplining yourself to do what you know is right and importance, although difficult, is the highroad to pride, self-esteem, and personal satisfaction.

(Saturn rising in Scorpio; Jupiter in Capricorn in the 2nd)Europe was created by history. America was created by philosophy.

I always cheer up immensely if an attack is particularly wounding because I think, well, if they attack one personally, it means they have not a single political argument left.

(Saturn rising in Scorpio)I am extraordinarily patient, provided I get my own way in the end.

(Saturn in Scorpio; Jupiter in Capricorn)I am in politics because of the conflict between good and evil, and I believe that in the end good will triumph.

(Moon and Neptune conjunct MC, in 9th, in Leo; Pluto opposition Jupiter)I do not know anyone who has got to the top without hard work. That is the recipe. It will not always get you to the top, but should get you pretty near.

(Saturn in Scorpio; Jupiter in Capricorn opposite Pluto in Cancer)I don't mind how much my Ministers talk, so long as they do what I say.

(Moon Neptune in Leo; Jupiter in Capricorn)I have made it quite clear that a unified Ireland was one solution that is out. A second solution was a confederation of two states. That is out. A third solution was joint authority. That is out-that is a derogation of sovereignty.

I just owe almost everything to my father and it's passionately interesting for me that the things that I learned in a small town, in a very modest home, are just the things that I believe have won the election.

I love argument, I love debate. I don't expect anyone just to sit there and agree with me, that's not their job.

(Mars, Mercury and Sun in Libra; Saturn in Scorpio; Uranus in the 5thI owe nothing to Women's Lib.

(Mars in Libra; Venus in Sagittarius)I seem to smell the stench of appeasement in the air.

(Moon Neptune in Leo)I shan't be pulling the levers there but I shall be a very good back-seat driver.

(Saturn in Scorpio; Jupiter Pluto opposition)I usually make up my mind about a man in ten seconds, and I very rarely change it.

(Mars in Libra; Venus in Sagittarius)If my critics saw me walking over the Thames they would say it was because I couldn't swim.

(Saturn in Scorpio)If you lead a country like Britain, a strong country, a country which has taken a lead in world affairs in good times and in bad, a country that is always reliable, then you have to have a touch of iron about you.

(Saturn in Scorpio)If you set out to be liked, you would be prepared to compromise on anything at any time, and you would achieve nothing.

If you want to cut your own throat, don't come to me for a bandage.

In politics, if you want anything said, ask a man; if you want anything done, ask a woman.

It is only when you look now and see success that you say that it was good fortune. It was not. We lost 250 of our best young men. I felt every one.

It may be the cock that crows, but it is the hen that lays the eggs.

It pays to know the enemy - not least because at some time you may have the opportunity to turn him into a friend.

(Mercury, Mars, and Sun in Libra in 11th)It was sheer professionalism and inspiration and the fact that you really cannot have people marching into other people's territory and staying there.

It's a funny old world.

(no kidding. Oh, uh, Venus in Sagittarius; Jupiter in Capricorn))It's passionately interesting for me that the things that I learned in a small town, in a very modest home, are just the things that I believe have won the election.

Mr. Clarke played the King all evening as though under constant fear that someone else was about to play the Ace.

No one would remember the Good Samaritan if he'd only had good intentions - he had money, too.

No woman in my time will be prime minister or chancellor or foreign secretary - not the top jobs. Anyway, I wouldn't want to be prime minister; you have to give yourself 100 percent.

Nothing is more obstinate than a fashionable consensus.

Of course it's the same old story. Truth usually is the same old story.

On my way here I passed a local cinema and it turned out you were expecting me after all, for the billboards read: The Mummy Returns.

One hopes to achieve the zero option, but in the absence of that we must achieve balanced numbers.

Ought we not to ask the media to agree among themselves a voluntary code of conduct, under which they would not say or show anything which could assist the terrorists' morale or their cause while the hijack lasted.

Pennies do not come from heaven. They have to be earned here on earth.

Platitudes? Yes, there are platitudes. Platitudes are there because they are true.

Power is like being a lady... if you have to tell people you are, you aren't.

Standing in the middle of the road is very dangerous; you get knocked down by the traffic from both sides.

Success is having a flair for the thing that you are doing; knowing that is not enough, that you have got to have hard work and a sense of purpose.

The battle for women's rights has been largely won.

There are still people in my party who believe in consensus politics. I regard them as Quislings, as traitors... I mean it.

There can be no liberty unless there is economic liberty.

There is no such thing as society: there are individual men and women, and there are families.

This lady is not for turning.

To cure the British disease with socialism was like trying to cure leukaemia with leeches.

To me, consensus seems to be the process of abandoning all beliefs, principles, values and policies. So it is something in which no one believes and to which no one objects.

To wear your heart on your sleeve isn't a very good plan; you should wear it inside, where it functions best.

Unless we change our ways and our direction, our greatness as a nation will soon be a footnote in the history books, a distant memory of an offshore island, lost in the mists of time like Camelot, remembered kindly for its noble past.

We didn't have to do the minuets of diplomacy. We got down to business.

We were told our campaign wasn't sufficiently slick. We regard that as a compliment.

What Britain needs is an iron lady.

What is success? I think it is a mixture of having a flair for the thing that you are doing; knowing that it is not enough, that you have got to have hard work and a certain sense of purpose.

Why do you climb philosophical hills? Because they are worth climbing. There are no hills to go down unless you start from the top.

You don't tell deliberate lies, but sometimes you have to be evasive.

You may have to fight a battle more than once to win it.

IBorn in 1925, Margaret Hilda Roberts was an enormously industrious girl. The daughter of a Grantham shopkeeper, she studied on scholarship, worked her way to Oxford and took two degrees, in chemistry and law. Her fascination with politics led her into Parliament at age 34, when she argued her way into one of the best Tory seats in the country, Finchley in north London. Her quick mind (and faster mouth) led her up through the Tory ranks, and by age 44 she got settled into the "statutory woman's" place in the Cabinet as Education Minister, and that looked like the summit of her career. But Thatcher was, and is, notoriously lucky. Her case is awesome testimony to the importance of sheer chance in history. In 1975 she challenged Edward Heath for the Tory leadership simply because the candidate of the party's right wing abandoned the contest at the last minute. Thatcher stepped into the breach. When she went into Heath's office to tell him her decision, he did not even bother to look up. "You'll lose," he said. "Good day to you."

But as Victor Hugo put it, nothing is so powerful as "an idea whose time has come." And by the mid-'70s enough Tories were fed up with Heath and "the Ratchet Effect"--the way in which each statist advance was accepted by the Conservatives and then became a platform for a further statist advance.

She chose her issues carefully--and, it emerged, luckily. The legal duels she took on early in her tenure as Prime Minister sounded the themes that made her an enduring leader: open markets, vigorous debate and loyal alliances. Among her first fights: a struggle against Britain's out-of-control trade unions, which had destroyed three governments in succession. Thatcher turned the nation's anti-union feeling into a handsome parliamentary majority and a mandate to restrict union privileges by a series of laws that effectively ended Britain's trade-union problem once and for all. "Who governs Britain?" she famously asked as unions struggled for power. By 1980, everyone knew the answer: Thatcher governs.

Once the union citadel had been stormed, Thatcher quickly discovered that every area of the economy was open to judicious reform. Even as the rest of Europe toyed with socialism and state ownership, she set about privatizing the nationalized industries, which had been hitherto sacrosanct, no matter how inefficient. It worked. British Airways, an embarrassingly slovenly national carrier that very seldom showed a profit, was privatized and transformed into one of the world's best and most profitable airlines. British Steel, which lost more than a billion pounds in its final years as a state concern, became the largest steel company in Europe.

By the mid-1980s, privatization was a new term in world government, and by the end of the decade more than 50 countries, on almost every continent, had set in motion privatization programs, floating loss-making public companies on the stock markets and in most cases transforming them into successful private-enterprise firms. Even left-oriented countries, which scorned the notion of privatization, began to reduce their public sector on the sly. Governments sent administrative and legal teams to Britain to study how it was done. It was perhaps Britain's biggest contribution to practical economics in the world since J.M. Keynes invented "Keynesianism," or even Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations.

But Thatcher became a world figure for more than just her politics. She combined a flamboyant willpower with evident femininity. It attracted universal attention, especially after she led Britain to a spectacular military victory over Argentina in 1982. She understood that politicians had to give military people clear orders about ends, then leave them to get on with the means. Still, she could not bear to lose men, ships or planes. "That's why we have extra ships and planes," the admirals had to tell her, "to make good the losses." Fidelity, like courage, loyalty and perseverance, were cardinal virtues to her, which she possessed in the highest degree. People from all over the world began to look at her methods and achievements closely, and to seek to imitate them.

One of her earliest admirers was Ronald Reagan, who achieved power 18 months after she did. He too began to reverse the Ratchet Effect in the U.S. by effective deregulation, tax cutting and opening up wider market opportunities for free enterprise. Reagan liked to listen to Thatcher's various lectures on the virtues of the market or the minimal state. "I'll remember that, Margaret," he said. She listened carefully to his jokes, tried to get the point and laughed in the right places.

They turned their mutual affection into a potent foreign policy partnership. With Reagan and Thatcher in power, the application of judicious pressure on the Soviet state to encourage it to reform or abolish itself, or to implode, became an admissible policy. Thatcher warmly encouraged Reagan to rearm and thereby bring Russia to the negotiating table. She shared his view that Moscow ruled an "evil empire," and the sooner it was dismantled the better. Together with Reagan she pushed Mikhail Gorbachev to pursue his perestroika policy to its limits and so fatally to undermine the self-confidence of the Soviet elite.

Historians will argue hotly about the precise role played by the various actors who brought about the end of Soviet communism. But it is already clear that Thatcher has an important place in this huge event.

It was the beginning of a new historical epoch. All the forces that had made the 20th century such a violent disappointment to idealists--totalitarianism, the gigantic state, the crushing of individual choice and initiative--were publicly and spectacularly defeated. Ascendant instead were the values that Thatcher had supported in the face of sometimes spectacular opposition: free markets and free minds. The world enters the 21st century and the 3rd millennium a wiser place, owing in no small part to the daughter of a small shopkeeper, who proved that nothing is more effective than willpower allied to a few clear, simple and workable ideas.

Thatcher, Margaret Hilda Roberts Thatcher, Baroness, 1925–, British political leader. Great Britain's first woman prime minister, Thatcher served longer than any other British prime minister in the 20th cent. In office she initiated what became known as the “Thatcher Revolution,” a series of social and economic changes that dismantled many aspects of Britain's postwar welfare state.

Thatcher studied chemistry at Oxford and later became a lawyer. Elected to Parliament as a Conservative in 1959, she held junior ministerial posts (1961–64) before serving (1970–74) as secretary of state for education and science in Edward Heath's cabinet. After two defeats in general elections, the Conservative party elected her its first woman leader in 1975.

After leading the Conservatives to an electoral victory in 1979, Thatcher became prime minister. She had pledged to reduce the influence of the trade unions and combat inflation, and her economic policy rested on the introduction of broad changes along free-market lines. She attacked inflation by controlling the money supply and sharply reduced government spending and taxes for higher-income individuals. Although unemployment continued to rise to postwar highs, the declining economic output was reversed. In 1982, when Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands, a British colony, Britain's successful prosecution of the subsequent war contributed to the Conservatives' win at the polls in 1983.

Thatcher's second government privatized national industries and utilities, including British Gas and British Telecommunications. Her antiunion policies forced coal miners to return to work after a year on strike. In foreign affairs, Thatcher was a close ally of President Ronald Reagan and shared his antipathy to Communism. She allowed the United States to station (1980) nuclear cruise missiles in Britain and to use its air bases to bomb Libya in 1986. She forged (1985) a historic accord with Ireland, giving it a consulting role in governing Northern Ireland.

In 1987 Thatcher led the Conservatives to a third consecutive electoral victory, although with a reduced majority. She proposed free-market changes to the national health and education systems and introduced a controversial per capita “poll tax” to pay for local government, which fueled criticisms that she had no compassion for the poor. Her refusal to support a common European currency and integrated economic policies led to the resignation of her treasury minister in 1989 and her deputy prime minister in 1990.

Disputes over the poll tax, which took effect in 1990, and over European integration led to a leadership challenge (1990) from within her party. She resigned as prime minister, and John Major emerged as her successor. In 1992 Thatcher retired from the House of Commons and was created Baroness Thatcher. In the mid-1990s Thatcher was publicly critical of Major's more moderate policies, and she has continued to criticize publicly Conservative and Labour positions she disagrees with.

The Right Honourable Period in Office: 4 May 1979 – 28 November 1990PM Predecessor: James CallaghanPM Successor: John MajorDate of Birth: 13 October 1925Place of Birth: Grantham, EnglandPolitical Party:

ConservativeRetirement honour: Knighthood of the Garter

Life Barony

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher, LG, OM, PC (born 13 October 1925) is a British politician and the first female Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, a position she held from 1979 to 1990. She is a member of the Conservative Party and the eponymous figurehead of a political ideology known as Thatcherism theoretically involving reduced government spending, lower taxes and regulation and a program of privatization of government-owned industries. Even before coming to power she was nicknamed The Iron Lady in Soviet propaganda because of her vocal opposition to communism, an appellation which stuck.

Thatcher served as Education Secretary in the government of Edward Heath from 1970 to 1974, and successfully challenged Heath for the Conservative leadership in 1975. She was undefeated at the polls, winning the 1979, 1983 and 1987 general elections, and became the longest-serving Prime Minister of the 20th century. In foreign relations, Thatcher maintained the "special relationship" with the United States, and formed a close bond with Ronald Reagan. Thatcher also dispatched a Royal Navy task force to retake the Falkland Islands from Argentina in the Falklands War.

The changes Thatcher set in motion as Prime Minister were profound, altering much of the economic and cultural landscape of Britain. She curtailed the power of the trade unions, cut back the role of the state in business, dramatically expanded home ownership, and in so doing created a more entrepreneurial culture. She also aimed to cut back the welfare state and foster a more flexible labor market that would create jobs and could adapt to market conditions. Exacerbated by the global recession of the early 1980s, her policies initially caused large-scale unemployment, especially in the industrial heartlands of northern England, and increased wealth inequalities. From the mid 1980s Thatcher's policies inaugurated a period of sustained economic growth that led to an improvement in Britain's economic performance relative to its European peers, after decades of relative decline.

Her popularity finally declined when she replaced the unpopular local government Rates tax with the even less popular Community Charge, more commonly known as the poll tax. At the same time the Conservative Party began to split over her sceptical approach to European Economic and Monetary Union. Her leadership was challenged from within and she was forced to resign in 1990, her loss at least partly due to inadequate advice and campaigning. In 1992 she was appointed Baroness Thatcher; since then her direct political work has been within the House of Lords and as head of the Thatcher Foundation.

Early life and education

Thatcher was born Margaret Hilda Roberts in the town of Grantham in Lincolnshire in eastern England. Her father was Alfred Roberts who ran a grocers' shop in the town and was active in local politics, serving as an Alderman (while officially described as 'Liberal Independent', in practice he supported the local Conservatives). When the Labour Party won control of Grantham Council in 1945, Alfred Roberts was not re-elected as an Alderman, a decision which affected Thatcher deeply.

She did well at school, going on to a boys' grammar school and then to Somerville College, Oxford from 1944 where she studied chemistry. She became Chairman of Oxford University Conservative Association in 1946, the third woman to hold the post. She obtained a second class degree and worked as a research chemist for British Xylonite and then Lyons & Company, where she helped develop methods for preserving ice cream. She was a member of the team that developed the first soft frozen ice cream.

Political career between 1950 and 1970

In the election of 1950 she was the youngest woman Conservative candidate but fought in the safe Labour seat of Dartford. She fought the seat again in the 1951 election. Her activity in the Conservative Party in Kent brought her into contact with Denis Thatcher; they fell in love and were married later in 1951. Denis Thatcher was a wealthy businessman and funded his wife to read for the Bar. She qualified as a Barrister in 1953, the same year that her twin children, Carol and Mark were born. On returning to work, she specialised in tax issues.

Thatcher had begun to look for a safe Conservative seat, and was narrowly rejected as candidate for Orpington in 1954. She had several other rejections before being selected for Finchley in April 1958. She easily won the seat in the 1959 election and took her seat in the House of Commons. Unusually, her maiden speech was made in support of her Private Member's Bill which was successful and forced local councils to hold meetings in public.

She was given an early promotion to the front bench as Parliamentary Secretary at the Ministry of Pensions and National Insurance in September 1961, keeping the post until the Conservatives lost power in the 1964 election. When Sir Alec Douglas-Home stepped down, Thatcher voted for Edward Heath in the leadership election over Reginald Maudling, and was rewarded with the job of Conservative spokesman on Housing and Land. She moved to the Shadow Treasury Team after 1966.

Thatcher was one of few Conservative MPs to support the Bill to decriminalise male homosexuality, and she voted in favour of the principle of David Steel's Bill to legalise abortion. However she was opposed to the abolition of capital punishment. She made her mark as a conference speaker in 1966 with a strong attack on the taxation policy of the Labour Government as being steps "not only towards Socialism, but towards Communism". She won promotion to the Shadow Cabinet as Shadow Fuel Spokesman in 1967, and was then promoted to shadow Transport and finally Education before the 1970 general election.

In Heath's Cabinet

When the Conservatives won the 1970 election, Thatcher became Secretary of State for Education and Science. In her first months in office, forced to administer a cut in the Education budget, she decided that abolishing free milk in schools would be less harmful than other measures. Nevertheless, this provoked a storm of public protest, earning her the nickname "Maggie Thatcher, milk snatcher", coined by The Sun. Her term was marked by many proposals for more local education authorities to abolish grammar schools and adopt comprehensive secondary education, of which she approved, even though this was widely seen as a left-wing policy. Thatcher also defended the budget of the Open University from attempts to cut it.

After the Conservative defeat in February 1974, she was again promoted to be Shadow Environment Secretary. In this job she promoted a policy of abolishing the rating system that paid for local government services, which proved a popular policy within the Conservative Party. However she agreed with Sir Keith Joseph that the Heath Government had lost control of monetary policy. After Heath lost the second election that year, Joseph and other right-wingers declined to challenge his leadership but Thatcher decided that she would. Unexpectedly she outpolled him on the first ballot and won the job on the second, in February 1975. She appointed Heath's preferred successor William Whitelaw as her Deputy.

As Leader of the Opposition

On 19 January 1976 she made a speech at Kensington Town Hall in which she made a scathing attack on the Soviet Union. The most controversial part of her speech ran:

"The Russians are bent on world dominance, and they are rapidly acquiring the means to become the most powerful imperial nation the world has seen. The men in the Soviet Politburo do not have to worry about the ebb and flow of public opinion. They put guns before butter, while we put just about everything before guns."

In response, the Soviet Defence Ministry newspaper Red Star gave her the nickname "The Iron Lady", which was soon publicised by Radio Moscow world service. She took delight in the name and it soon became associated with her image as an unwavering and steadfast character. She acquired many other nicknames such as "The Great She-Elephant", "Attila the Hen", and "The Grocer's Daughter". The last nickname was due to her father's profession, but coined at a time when she was considered as Edward Heath's ally; he had been nicknamed "The Grocer" by Private Eye.

At first she appointed many Heath supporters in the Shadow Cabinet and throughout her administrations sought to have a cabinet that reflected the broad range of opinions in the Conservative Party. Thatcher had to act cautiously in converting the Conservative Party to her monetarist beliefs. She reversed Heath's support for devolution to Scotland. An interview she gave to Granada Television's World in Action programme in 1978, in which she spoke of her concerns about immigrants "swamping" Britain, aroused particular controversy as immigration was a substantial party issue at that time. Most opinion polls showed that voters preferred James Callaghan as Prime Minister even when the Conservative Party was in the lead, but the Labour Government's severe difficulties with the Trades Unions over the winter of 1978–1979, dubbed the 'Winter of Discontent', put the Conservatives well ahead in the 1979 election and Thatcher became the first female Prime Minister.As Prime Minister

1979–1983

Thatcher and President Reagan at Camp David.

She formed a government on 4 May 1979, with a mandate to reverse Britain's economic decline and to reduce the extent of the state. Thatcher was incensed by one contemporary view within the Civil Service that its job was to manage Britain's decline from the days of Empire, and wanted the country to punch above its weight in international affairs. She was a philosophic soulmate with Ronald Reagan, elected in 1980 in the United States, and to a lesser extent Brian Mulroney, who was elected around the same time in Canada. It seemed for a time that conservatism might be the dominant political philosophy in the major English-speaking nations for the era.

In 1981 IRA prisoners in Long Kesh prison went on hunger strike to regain the status of political prisoners, which had been revoked shortly before. Bobby Sands, the first of the strikers, was elected as an MP for the constituency of Fermanagh-South Tyrone a few weeks before his death. Thatcher refused at first to countenance a return to political status for the IRA men, famously declaring "A crime is a crime". However after nine more men starved themselves to death, and in the face of growing anger on both sides of the Irish border she finally allowed IRA prisoners political status. The anger generated during this crisis led indirectly to Sinn Féin's later successes and was a powerful morale boost for a demoralised IRA.

Thatcher also initiated a policy of "Ulsterisation", believing that the unionists of Ulster should be to the forefront in combating Irish republicanism. This meant relieving the burden on the mainstream British army and elevating the role of the Ulster Defence Regiment and the Royal Ulster Constabulary.

Thatcher began by increasing interest rates to drive down the money supply. She had a preference for indirect taxation over taxes on income, value added tax (VAT) rose sharply to 15% with the result that inflation initially rose. These moves hit businesses, especially in the manufacturing sector, and unemployment quickly passed two million. However her early tax policy reforms were based on supply-side economics. There was a severe recession in the early 1980s, and the Government's economic policy was widely blamed. Political commentators harked back to the Heath Government's "U-turn" and speculated that Mrs Thatcher would follow suit, but she repudiated this approach at the 1980 Conservative Party conference, telling the party "You turn if you want to. The lady's not for turning". That she meant what she said was confirmed in the 1981 budget, when despite an open letter from 364 economists, taxes were increased in the middle of a recession. Though unemployment reached 3 million in January 1982, the inflation rate dropped in to single figures and interest rates were able to fall. By the time of the 1983 election the economy was re-stabilising on a new norm, and was far stronger in economic and entrepreneurial terms than previously. This low inflation approach became copied widely.

On 2 April 1982, Argentine forces invaded the Falkland Islands, a British territory claimed by Argentina. Thatcher immediately sent a naval task force to the Falklands and ordered the sinking of the Belgrano (an Argentine ship sailing away from the Falkland Islands)to instiagate a war, which defeated the Argentines, resulting in a wave of patriotic enthusiasm for her personally, even though her popularity before the war was at an all time low for a serving Prime Minister. The landslide victory of the Conservatives in the June 1983 general election is often ascribed to the 'Falklands Effect'. Her 'Right to Buy' policy of allowing residents of council housing to buy their homes at a discount did much to increase her popularity in working-class areas, although this meant that a housing shortage was to develop for those unable to do so.

1983–1987

Thatcher was committed to reducing the power of the trade unions but, unlike the Heath government, proceeded by way of incremental change rather than a single Act. Several unions decided to launch strikes which were wholly or partly aimed at damaging her politically. The most significant of these was carried out by the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM). Thatcher had made preparations for the NUM strike by building up coal stocks. As a result, there were no cuts in electric power. Picket line violence, coupled with the fact that the NUM had not held a ballot to approve strike action, contrived to swing public opinion on her side - although predominantly in the South. The Miners' Strike lasted a full year (1984–1985) before the miners were forced to give in and go back to work without a deal. After this strike, trade union resistance to reform was much reduced and a succession of changes were made.

On the early morning of 12 October 1984, Thatcher escaped injury from a bomb planted by the Provisional Irish Republican Army in Brighton's Grand Hotel during the Conservative Party conference. Five people died in the attack, including the wife of the government's Chief Whip, John Wakeham. A prominent member of the Cabinet, Norman Tebbit, was injured, along with his wife, Margaret, who was left paralyzed. Thatcher insisted that the Conference open on time the next day and made her speech as planned.

Thatcher's political and economic philosophy emphasised free markets and entrepreneurialism. Since gaining power, she had experimented in selling off a small nationalised industry, the National Freight company, to the public, with a surprisingly large response. After the 1983 election, the Government became bolder and sold off most of the large utilities which had been in public ownership since the late 1940s. Many in the public took advantage of share offers, although many sold their shares immediately for a quick profit. The policy of privatisation became synonymous with Thatcherism and has since been exported across the globe.

In the Cold war Mrs Thatcher supported Ronald Reagan's policies of deterrence against the Soviets. United States forces were permitted by Mrs Thatcher to station nuclear cruise missiles at British bases, arousing mass protests by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. She had no objections to the US bombing raid on Libya from bases in Britain in 1986, and her liking for defence ties with the United States was demonstrated in the Westland affair when she acted with colleagues to prevent the helicopter manufacturer Westland, a vital defence contractor, from linking with the Italian firm Agusta in favour of a link with Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation of the United States. Defence Secretary Michael Heseltine, who had pushed the Agusta deal, resigned in protest at her style of leadership, and thereafter became a potential leadership challenger.

In 1985, the University of Oxford voted to refuse her an honorary degree in protest against her cuts in funding for education. [1] (http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/low/dates/stories/january/29/newsid_2506000/2506019.stm) This award had always previously been given to Prime Ministers who had been educated at Oxford.

In 1986, 's government controversially abolished the Greater London Council (GLC), led by Ken Livingstone, and six Metropolitan County Councils (MCCs). The government claimed this was an efficiency measure. However it is widely believed to have been politically motivated as all of the abolished councils were controlled by Labour, and had become powerful centres of opposition to her government.

Between 1983 and 1987, Thatcher had two noted foreign policy successes. In 1984 she visited China and signed the Sino-British Joint Declaration with Deng Xiaoping on 19 December stating the basic policies of the People's Republic of China regarding Hong Kong after the handover in 1997. At the Fontainebleau summit of 1984, Thatcher argued that the United Kingdom paid far more to the European Economic Community than it received in spending and negotiated a budget rebate. She was widely quoted as saying "We want our money back".

1987–1990

By winning the 1987 general election she became the first Prime Minister of the United Kingdom to win three consecutive general elections since Lord Liverpool, who was in office from 1812–1827. Most United Kingdom newspapers supported her, with the exception of The Daily Mirror and The Guardian, and were rewarded with regular press briefings by her press secretary, Bernard Ingham. She was known as "Maggie" in the tabloids, which in turn led to the well-known "Maggie Out!" protest song, sung throughout that period by some of her opponents. She was also felt to have created a significant North-South divide between the "haves" and the "have nots" since the South was the main beneficiary of new Financial and Service industries, and the North was hit hard by poverty and mass unemployment due to loss of traditional heavy industries such as mining, steel production and ship building.

In the late 1980's Thatcher began to be concerned by environmental policy, which she had previously dismissed. In 1988 she made a major speech accepting the problems of global warming, ozone depletion and acid rain [2] (http://www.margaretthatcher.org/speeches/displaydocument.asp?docid=107346) and in 1990 she opened the Hadley Centre for climate prediction and research that she had caused to be founded [3] (http://www.margaretthatcher.org/Speeches/displaydocument.asp?docid=108102&doctype=1).

At Bruges in 1988 Thatcher made a speech in which she outlined her opposition to proposals from the European Communities for a federal structure and increasing centralisation of decision-making. Although she had supported British membership, Thatcher believed that the role of the EC should be limited to ensuring free trade and effective competition, and feared that new EC regulations would reverse the changes she was making in Britain. She was specifically against Economic and Monetary Union, through which a single currency would replace national currencies, and for which the EC was making preparations.

Thatcher started to lose popularity in 1989, as the economy suffered from high interest rates imposed to stop an unsustainable boom. She blamed her Chancellor, Nigel Lawson, who had been following an economic policy which was a preparation for monetary union; Thatcher claimed not to have been told and did not approve. At the Madrid European summit, Lawson and Foreign Secretary Geoffrey Howe forced Thatcher to agree the circumstances in which she would join the Exchange Rate Mechanism, a preparation for monetary union. Thatcher took revenge on both by demoting Howe and listening more to her adviser Sir Alan Walters on economic matters. Lawson resigned that October, feeling that Thatcher had undermined him.

That November Thatcher was challenged for the leadership of the Conservative Party by Sir Anthony Meyer. As Meyer was a virtually unknown backbench MP, he was viewed as a "stalking horse" candidate for more prominent members of the party. Thatcher easily defeated Meyer's challenge, but there were sixty ballot papers either cast for Meyer or abstaining, a surprisingly large number.

Thatcher's new system to replace local government rates was introduced for Scotland in 1989 and for England and Wales in 1990. These were replaced by the "Community Charge" (more widely known as the Poll Tax) which applied at the same amount to every individual resident, with only limited discounts for low earners. This was to be the most unpopular policy of her premiership. The Charge was introduced early in Scotland as the rateable values would in any case have been reassessed in 1989; however, it led to accusations that Scotland was a 'testing ground' for the tax. Thatcher apparently believed that the new tax would be popular, and had been persuaded by Scottish Conservatives to bring it in early and in one go. Despite her hopes, the early introduction led to a sharp decline in the popularity of the Conservative party in Scotland.

Additional problems emerged when many of the tax rates set by local councils proved to be much higher than many earlier predictions. Some have argued that local councils saw the introduction of the new system of taxation as the opportunity to make significant increases in the amount taken, assuming (correctly) that it would be the originators of the new tax system and not its local operators who would be blamed.

A large London demonstration against the poll tax on 31 March 1990, which was the day before it was introduced in England and Wales, turned into a riot. Millions of people resisted paying the tax. Opponents of the tax banded together to resist bailiffs and disrupt court hearings of poll tax debtors. Mrs Thatcher refused to compromise, or change the tax, and its unpopularity was a major factor in Thatcher's downfall. One of her final acts in office was to pressure US President George H. W. Bush to deploy troops to the Middle East to drive Saddam Hussein's army out of Kuwait. Bush was somewhat apprehensive about the plan, but Thatcher famously told him that this was "no time to go wobbly!"

On the Friday before the Conservative Party conference in October 1990, Thatcher persuaded her new Chancellor John Major to reduce interest rates by 1%. Major persuaded her that the only way to maintain monetary stability was to join the Exchange Rate Mechanism at the same time, despite not meeting the 'Madrid conditions'. The conference that year saw a degree of unity break out within the Conservative Party. Few who attended could have realised that Mrs Thatcher had only a matter of weeks left in office.

Fall from power

Thatcher

By 1990 opposition to Thatcher's policies on local government taxation, her Government's perceived mis-handling of the economy (especially high interest rates of 15% which were undermining her core voting base within the home-owning, entrepreneurial and business sectors), the divisions opening within her party and in the broader political landscape over the appropriate handling of European integration due to Thatcher's Euroscepticism, the growing internal strife within her party that was partly seen as stemming from her leadership, and her perceived arrogance in ignoring others' views, made her and her party seem increasingly politically vulnerable to internal challenge.

A challenge was precipitated by the resignation of Sir Geoffrey Howe on 1 November, whom Thatcher had been humiliating in Cabinet meetings. Howe condemned Thatcher's policy on the European Communities and openly invited "others to consider their own response", which led Michael Heseltine to announce his challenge for party leadership (and hence Prime Minister). In the first ballot, Thatcher was two votes short of winning automatic re-election, a small but critical margin.

This was probably at least in part due to mismanagement; she had fatally decided to be out of the country at a conference in Paris, and her advisors appear to have underestimated the seriousness of the matter and the need to campaign, reassure and cajole potentially wavering supporters that would achieve the necessary first round win and put paid to talk of doubts. On consulting with cabinet colleagues, a large majority felt that, the first round not being a clear win, she would lose the second run-off ballot.

On 22 November, at just after 9:30 AM, Mrs Thatcher announced that she would not be a candidate in the second ballot and therefore her term of office would come to an end. She supported John Major as her successor, and retired from Parliament at the 1992 election.

Post-political career

In 1992 she was made Baroness Thatcher of Kesteven in the County of Lincolnshire, and entered the House of Lords. In addition, Denis Thatcher, her husband, had been given a Baronetcy in 1991 (ensuring that their son, Mark, would inherit a title). In July of that year, she was also hired by tobacco giant Philip Morris Companies, now the Altria Group, as a "geopolitical consultant" for US$250,000 per year and an annual contribution of US$250,000 to her Foundation. In practice, she helped them break into markets in central Europe, the former Soviet Union, China, and Vietnam, as well as fight against a proposed EC ban on tobacco advertising.

She wrote her memoirs in two volumes. Although she remained supportive in public, in private she made her displeasure with many of John Major's policies plain, and her views were conveyed to the press and widely reported. Major later said he found her behaviour in retrospect to have been intolerable. She publicly endorsed William Hague for the Conservative leadership in 1997.

Lady Thatcher visits Pinochet during house arrest in London, in 1998.

In 1998 she made a highly publicised and controversial visit to the former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet during the time he was under house arrest in London facing charges of torture, conspiracy to torture and conspiracy to murder, and expressed her support and friendship for him.[4] (http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/304516.stm).

She made many speaking engagements around the world, and actively supported the Conservative election campaign in 2001. However, on 22 March 2002 she was told by her doctors to make no more public speeches on health grounds, having suffered several small strokes which left her in a very frail state. In 2003 she visited Mayor Michael Bloomberg of New York City and compared his offices to those of Winston Churchill's War Room. Although she was able to attend the funeral in June 2004 of former US President Ronald Reagan, her eulogy for him was pre-taped to prevent undue stress.

She remains involved with various Thatcherite groups, including being president of the Conservative Way Forward group, who held a dinner at the Savoy Hotel in honour of the 25th Anniversary of her election. She is honorary president of the Bruges Group, which takes its name from her 1988 speech at Bruges where she was first openly hostile to developments in the European Union. She is also patron of the Eurosceptic European Foundation founded by the Conservative MP Bill Cash. She was widowed on 26 June 2003.

Legacy

Thatcher at the Kennedy Space Center in February, 2001

Many United Kingdom citizens remember where they were and what they were doing when they heard that had resigned and what their reaction was. She brings out strong responses in people. Some people credit her with rescuing the British economy from the stagnation of the 1970s and admire her committed radicalism on social issues. Others see her as authoritarian and egotistical. She is accused of dismantling of the Welfare State and of destroying much of Britain's manufacturing base. The first charge reflects her government's rhetoric more than its actions, as it actually did little to reduce welfare expenditure, despite its desire to do so. The second charge is credible in that there was a major fall in manufacturing employment, and some industries almost disappeared, but her supporters would argue that that was necessary to modernise the British economy. Britain was widely seen as the "sick man of Europe" in the 1970s, and some argued that it would be the first developed nation to return to the status of a developing country. Instead, Britain emerged with a comparatively healthy economy, at least by previous standards. Her supporters claim that this was due to 's policies.

Critics of this view believe that the economic problems of the 1970s were exaggerated, and were caused largely by factors outside any UK government's control, such as high oil prices caused by the oil crisis which led to high inflation and damaged the economies of nearly all major industrial countries. Accordingly, they also argue that the economic downturn was not the result of socialism and trade unions, as Thatcherite supporters claim. Critics also argue that the Thatcher period in government coincided with a general improvement in the world economy, and the buoyant tax revenues from North Sea oil, and that these were the real cause of the improved economic environment of the 1980s rather than 's policies.

Perceptions of are mixed in the view of the British public. A clear illustration of the divisions of opinion over Thatcher's leadership can be found in recent television polls: Thatcher appears at Number 16 in the 2002 List of "100 Greatest Britons", which was the highest placing for a living person. She also appears at Number 3 in the 2003 List of "100 Worst Britons", which was confined to only those living, narrowly missing out on the top spot, which went to Tony Blair. In the end, however, few could argue that here was a woman who played a more important role on the world stage in the Twentieth Century, and even the Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair has implicitly and explicitly acknowledged her importance by continuing many of her economic policies.

Another view divides her economic legacy in two parts: market efficiency and long-term growth. The first part, due to her reforms, is considered good. Evidence for this is the low unemployment rate, due to labour market reforms, such as her laws for trade union weakening and refusal of a minimum wage, or deregulation of financial markets, which has helped the City retain her leader position as the main European financial center, or her push for increased competition in telecommunications and other public utilities businesses, while long-term growth, according to available data is considered low, due to lack of civil research and development spending, low education standards and uneffective job training policies.

Many of her policies have proved to be divisive. In Scotland, Wales and the urban and former mining areas of northern England she is still unpopular and many retain strong feelings about her. Many people remember the hardships of the miners strike, which destroyed many mining communities, and the decline of industry as service industries boomed. This was reflected in the 1987 general election, which she won by a landslide through winning large numbers of seats in southern England and the rural farming areas of northern England while winning few seats in the rest of the country.

Perceptions abroad broadly follow the same political divisions. On the left, is generally regarded as somebody who used force to quash social movements, and imposed social reforms that disregarded the interests of the working class and instead favoured the middle class and business. Satirists have often caricatured her; for instance, French singer Renaud wrote a song, Miss Maggie, which lauded women as refraining from many of the silly behaviors of males – and every time making an exception for "Mrs Thatcher". She will be remembered, too, for famously declaring in a 1987 interview that "there is no such thing as society" [5] (http://briandeer.com/social/thatcher-society.htm). On the economically liberal right Thatcher is often remembered with some fondness as somebody who dared to confront powerful unions and removed harmful constraints on the economy, though many do not openly claim to be following her example given the strong feelings that Mrs Thatcher elicits in many.

Her son, Sir Mark Thatcher, has been dogged by a series of controversies. As of late 2004, he was under house arrest in South Africa facing charges of abetting a coup attempt in Equatorial Guinea. These reports have been received with considerable schadenfreude by those in Britain less than impressed by the Thatcher legacy.

Titles and honours

Titles from birth

Here is a list of titles the Baroness Thatcher held from birth in chronological order:

• Miss Margaret Roberts (1925-1951)

• Mrs. Denis Thatcher (1951-1970)

• The Right Honourable (1970-1992)

• The Right Honourable Lady Thatcher (1992-1992)

• The Right Honourable The Baroness Thatcher (since 1992)

Honours

• Lady of the Most Noble Order of the Garter

• Order of Merit

• Privy Councillor

• Fellow of the Royal Society

I

I