Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2006

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images and Physiognomic Interpretations

Jesus does not give recipes that show the way to God as other teachers of religion do. He is himself the way.

Conscience is the perfect interpreter of life.

Man can certainly flee from God... but he cannot escape him. He can certainly hate God and be hateful to God, but he cannot change into its opposite the eternal love of God which triumphs even in his hate.

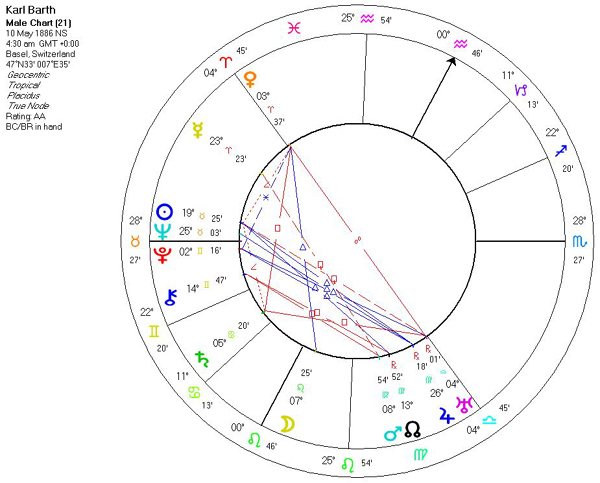

(Venus square Saturn. Neptune conjunct Pluto & Ascendant.)Whether the angels play only Bach praising God, I am not quite sure. I am sure, however, that en famille they play Mozart.

Man can certainly keep on lying … but he cannot make truth falsehood. He can certainly rebel … but he can accomplish nothing which abolishes the choice of God.

The best theology would need no advocates: it would prove itself.

Religion is the possibility of the removal of every ground of confidence except confidence in God alone.

Laughter is the closest thing to the grace of god.

We have before us the fiendishness of business competition and the world war, passion and wrongdoing, antagonism between classes and moral depravity within them, economic tyranny above and the slave spirit below.

There is joy in heaven over one sinner that repenteth, more than over ninety and nine just persons, which need no repentance. But what is Repentance? Not the last and noblest and most refined achievement of the righteousness of men in the service of God, but the first elemental act of the righteousness of God in the service of men; the work that God has written in their hearts and which, because it is from God and not from men, occasions joy in heaven; that looking forward to God, and to Him only, which is recognized only by God and by God Himself.

Commemoration of Peter Chanel, Religious, Missionary in the South Pacific, Martyr, 1841

The Day of Jesus Christ is the Day of all days; the brilliant and visible light of this one point is the hidden invisible light of all points; to perceive the righteousness of God once and for all here is the hope of righteousness (Gal. 5:5) everywhere and at all times. By the knowledge of Jesus Christ all human waiting is guaranteed, authorized and established; for He makes it known that it is not men who wait, but God -- in His faithfulness.Commemoration of Samuel & Henrietta Barnett, Social Reformers, 1913 & 1936 Religion is the possibility of the removal of every ground of confidence except confidence in God alone.

[From our side] our relation to God is unrighteous. Secretly we are ourselves the masters in this relationship. We are not concerned with God, but with our own requirements, to which God must adjust Himself. Our arrogance demands that, in addition to everything else, some super-world should also be known and accessible to us. Our conduct calls for some deeper sanction, some approbation and remuneration from another world. Our well-regulated, pleasurable life longs for some hours of devotion, some prolongation into infinity. And so, when we set God upon the throne of the world, we mean by God ourselves. In "believing" on Him, we justify, enjoy, and adore ourselves.

Feast of Ignatius, Bishop of Antioch, Martyr, c.107

Grace is the incomprehensible fact that God is well pleased with a man, and that a man can rejoice in God. Only when grace is recognized to be incomprehensible is it grace. Grace exists, therefore, only where the Resurrection is reflected. Grace is the gift of Christ, who exposes the gulf which separates God and man, and, by exposing it, bridges it.Only one thing is quite certain: he too has his time and not more than his time. One day others will come who will do the same things better. And some day he will have been completely forgotten--even if he should have built the pyramids or the St. Gotthard tunnel or invented atomic fission. And one thing is even more certain: whether the achievement of a man's life is great or small, significant or insignificant, he will one day stand before his eternal judge, and everything that he has done and performed will be no more than a mole hill, and then he will have nothing better to do than hope for something he has not earned: not for a crown, but quite simply for gracious judgment which he has not deserved. That is the only thing that will count then, achievement or not. "My kindness shall not depart from you." By this man lives. By this alone can he live.

We may all be inclined to think of man's countless foolish and selfish intentions, his twisted and mischievous words and deeds. From all these, sin can be known, as a tree can be known from its fruits. Yet these outward signs are not sin itself, the wages of which are death. Sin is not confined to the evil things we do. It is the evil within us, the evil which we are. Shall we call it our pride or our laziness, or shall we call it the deceit of our life? Let us call it for once the great defiance which turns us again and again into the enemies of God and of our fellowmen, even of our own selves.

Feast of Martin, Monk, Bishop of Tours, 397

People naturally do not shout it out, least of all into the ears of us ministers; but let us not be deceived by their silence. Blood and tears, deepest despair and highest hope, a passionate longing to lay hold of ... Him who overcomes the world because He is its Creator and Redeemer, its beginning and ending and lord -- a passionate longing to have the word spoken, the word which promises grace in judgment, life in death, and the beyond in the here and now, God's word -- this it is that animates our church-goers.Commemoration of Birinus, Bishop of Dorchester (Oxon), Apostle of Wessex, 650 "Homesickness for the [One True Church]" is genuine and legitimate only in so far as it is a disquietude at the fact that we have lost and forgotten Christ, and with Him have lost the unity of the Church. Thus we must be on our guard, all along the line, lest the motives which stir us today lead us to a quest that looks past Him. Indeed, however rightful and urgent those motives are, we could well leave them out of our reckoning. We shall do well to realize that in themselves they are well-meaning but merely human desires, and that we can have no final certainty that they are rightful, no unanswerable claim for their fulfillment. Unless we regard them with a measure of holy indifference, we are ill placed for a quest after the unity of the Church.

Joy is the simplest form of gratitude.

In the Church of Jesus Christ there can and should be no non-theologians.

Jesus does not give recipes that show the way to God as other teachers of religion do. He is himself the way.

It is always the case that when the Christian looks back, he is looking at the forgiveness of sins.

Faith is never identical with piety.

Grace must find expression in life, otherwise it is not grace.

Mozart's music always sounds unburdened, effortless, and light. This is why it unburdens, releases, and liberates us.

Men have never been good, they are not good and they never will be good.

What God chooses for us children of men is always the best.

Faith in God's revelation has nothing to do with an ideology which glorifies the status quo.

(Venus opposition Uranus.)No one can be saved--in virtue of what he can do. Everyone can be saved--in virtue of what God can do.

(Neptune conjunct Sun & Ascendant.)All sin has its being and origin in the fact that man wants to be his own judge. And in wanting to be that, and thinking and acting accordingly, he and his whole world is in conflict with God. It is an unreconciled world, and therefore a suffering world, a world given up to destruction.”

(Saturn in Cancer.)[Karl Barth, the 20th-century theologian who pounded home the theme of God's sovereignty, saw no contradiction at all in a God who chooses to let prayers affect him.] He is not deaf, he listens; more than that, he acts. He does not act in the same way whether we pray or not. Prayer exerts an influence upon God's action, even upon his existence. That is what the word 'answer' means. ... The fact that God yields to man's petitions, changing his intentions in response to man's prayer, is not a sign of weakness. He himself, in the glory of his majesty and power, has so willed it.”

The relation of this God with this man; the relation of this man with this God--this is the only theme of the Bible and of philosophy.

Der Romerbrief [Philosophy]

Born in Basel, he spent his childhood years in Bern. From 1911 to 1921 he served as pastor in the village of Safenwil in the canton Argovia. Later he was professor of theology in Germany. He had to leave Germany in 1935 after he refused to swear allegiance to Adolf Hitler. Barth went back to Switzerland and became professor in Basel.

Karl Barth is considered by some the greatest Protestant theologian of the 20th century and possibly the greatest since the Reformation. More than anyone else, Barth inspired and led the renaissance of theology that took place from about 1920 to 1950. The son of the Swiss Reformed minister and New Testament scholar Fritz Barth, Karl Barth was born in Basel, May 10, 1886, and was reared in Bern, where his father taught. From 1904 to 1909, he studied theology at the universities of Bern, Berlin, Tübingen, and Marburg. In 1913 he married Nelly Hoffman; they had five children. Barth became known as a radical critic both of the prevailing liberal theology and of the social order. Liberal theology, Barth believed, had accommodated Christianity to modern culture. The crisis of World War I was in part a symptom of this unholy alliance. In his famous commentary Epistle to the Romans (1919; trans. 1933), Barth stressed the discontinuity between the Christian message and the world. He rejected the typical liberal points of contact between God and humanity in feeling or consciousness or rationality, as well as Catholic tendencies to trust in the church or spirituality.

Barth held professorships successively at Göttingen and Münster universities from 1923 to 1930, when he was appointed professor of systematic theology at the University of Bonn. He engaged in controversy with Adolf von Harnack, holding that the latter's scientific theology is only a preliminary to the true task of theology, which is identical with that of preaching. He opposed the Hitler regime in Germany and supported church-sponsored movements against National Socialism; he was the chief author of the Barmen Declaration, six articles that defined Christian opposition to National Socialist ideology and practice. In 1934 he was expelled from Bonn and returned to Switzerland; from 1935 until his retirement in 1962 was professor at Basel, exercising a worldwide influence. During this period he worked on his Church Dogmatics (1932-68), a multivolume work of great richness that was unfinished at his death. He remained in Basel until his death, December 10, 1968.

The principal emphasis in Barth's work, known as neoorthodoxy and crisis theology, is on the sinfulness of humanity, God's absolute transcendence, and the human inability to know God except through revelation. His objective was to lead theology away from the influence of modern religious philosophy back to the principles of the Reformation and the prophetic teachings of the Bible. He regarded the Bible, however, not as the actual revelation of God but as only the record of that revelation. For Barth, God's sole revelation of himself is in Jesus Christ. God is the "wholly other," totally unlike mankind, who are utterly dependent on an encounter with the divine for any understanding of ultimate reality. Barth saw the task of the church as that of proclaiming the "good word" of God and as serving as the "place of encounter" between God and mankind. Barth regarded all human activity as being under the judgment of that encounter.

Barth's first attempt at dogmatics was a volume of a Christian Dogmatics, published in 1927, which he judged to be a false start. Then in his study of Anselm of Canterbury he found a catalyst leading to what he called a breakthrough. He discovered in Anselm's "faith seeking understanding" that theology did not have to justify itself by some outside criterion; it has its own rationality and internal coherence in the form of witness to the event of Jesus Christ. This gave him confidence in his study of the gospel and in the fact that theology was a fully rational procedure, and he began his Church Dogmatics.

The Church Dogmatics is in four "volumes," each comprising between two and four large tomes. Volume I is on the doctrine of the Word of God. Volume I/1 is about the three forms of the Word of God (preached, written, and revealed) and the nature of the Trinity. Volume I/2 treats the three forms in more detail -- the revealed form in the incarnation of the Word of Jesus Christ, the written form in Scripture and the preached form in church proclamation.

Volume II is on the doctrine of God. Volume II/1 treats the knowledge of God, the main emphasis being on God's initiative in revealing himself. Then Barth treats the reality of God. He describes God as "one who loves in freedom," and there is an exposition of the "perfections of the divine loving" (grace, holiness, mercy, righteousness, patience, and wisdom), and the "perfections of the divine freedom" (unity, omnipresence, constancy, omnipotence, eternity, and glory). Volume II/2 is on the election of God, Barth's term for predestination. Barth transforms the doctrine of his own Calvinist tradition of double predestination by centering rejection and election in Jesus Christ, who takes all rejection on himself and also both elects all and is himself elected. Christ's election leads to the election of the community of Israel and the church, and only in that context is it right to talk about the election or rejection of the individual.

Volume III is on the doctrine of creation. Volume III/1 is on God's work of creation, its goodness and the relation of creation to God's covenant. Volume III/2 is on human being. Jesus Christ is the "real" human being and the criterion for true humanity. Volume III/3 covers providence, evil as an "impossible possibility" which has no future, and heaven, angels, and demons. Volume III/4 treats the ethical side of the doctrine of creation. God gives the freedom to live in gratitude before God, with other people, in respect for life and in limitation.

Barth completed the first three parts of Volume IV and partially completed part 4. Considering the doctrine of reconciliation, in Volume IV he interweaves the themes of Christology, sin, soteriology, pneumatology, ecclesiology, justification, sanctification, and vocation. Christ is the servant, the judge who is judged in our place and who empties himself, the royal man who is raised up by God; He is the true witness, the victor over all that opposes him, and the light of life. Specific aspects of sin are exposed by each aspect of Christ -- pride resists accepting what God become man does for us; sloth refuses to take an active part in the new life given by Christ; falsehood resists and distorts the witness of Christ. The way of human salvation is justification by faith through which the Christian community is gathered, sancification in love through which the community is built up, and vocation in hope, which sends the community out as witnesses in word and life. Barth did not live to write any of the projected final Volume V on eschatology.

Although Barth's uncompromising positions were a great strength during the period of Nazi power, his views were increasingly subjected to criticism in the following decades. Some argue that he was too negative in his estimate of mankind and its reasoning powers and too narrow in limiting revelation to the biblical tradition, thus excluding the non-Christian religions. He gives such radical priority to God's activity that some critics find human activity and freedom devalued. Barth sees revelation and salvation as given by God and valid quite apart from the subjective responses of human beings, and this is questioned as regards how far it takes account of the importance of human response to God. Barth's realism apparently aroused controversy; Barth takes a middle way between literalism (a one-to-one correspondence between our language and God) and pure symbolism or expressivism (no real preference at all). He takes a similar position on the historicity of the Gospel narratives; they are not necessarily literal history, nor are they myth or fiction.

Among Barth's other better known works are The Word of God and the Word of Man (1924; trans. 1928), Credo (1935; trans. 1936), and Evangelical Theology, an Introduction (1962; trans. 1963). His works have influenced many theologians positively and negatively, including Rudolf Bultmann, Paul Tillich, Hans Urs von Balthasar, Hans Küng, Jürgen Moltmann, Wolfhart Pannenberg, Eberhard Jüngel, and many theologians from beyond continental Europe.Karl Barth (1886-1968)

Karl Barth is widely regarded as one of the most influential Christian theologians. He is often acknowledged as the greatest Protestant theologian of this century. His major contribution was a radical change in the direction of theology from a 19th-century orientation toward progress to an orthodoxy that had to cope with the grim realities of the 20th century. His rejection of liberal theology led to an emphasis on the eschatological and supernatural in Christianity. He refused any synthesis between the church and culture, and emphasized the radical disjunction between God and human being.

Karl Barth was born in Basel, Switzerland, on May 10, 1886. He was raised in Bern where his father Fritz Barth, a Swiss Reformed minister and professor of New Testament and early church history, taught. From 1904 to 1909, Barth studied theology in Bern, Berlin, Tübingen, and Marburg. At Berlin he took part in the liberal theologian Adolf von Harnack's seminar, and at Marburg he came under the influence of Wilhelm Herrmann and became interested in the work of Friedrich Schleiermacher.

Barth went into the parish ministry from 1911 to 1921 (first an assistant pastor in Geneva, then pastor to the working-class parish of Safenwil). In 1913 he married Nelly Hoffman, a talented violinist; they had five children. The 10 years in Safenwill were the formative period of his life. Here Barth experienced conversion from culture Christianity. Barth quickly noticed that he often preached to no more than a dozen parishioners. One day he visited a sick, elderly man in the parish. When Barth asked him to which church he belonged, the man responded resentfully: "Pastor, I've always been an honest man. I've never been to church, and I've never been in trouble with the police." Barth recognized that this man was representative of majority of people in that society with the same basic pattern of scant attendance at worship services and disinterest in church religion. In this context Barth was convinced to reconsider the "culture Christianity" represented by the liberal theology in which he had been trained.

It was in Safenwil during World War I that Barth reviewed his theology along with a neighboring pastor and student-friend, Eduard Thurneysen, who was experiencing a similar crisis. Barth was shocked at the conduct of his liberal teachers when they were confronted with the social and political situation of wartime Europe. He read the "Declaration of German Intellectuals," calling for loyalty to Kaiser and Vaterland. How could this happen? It happened, he argued, because of a fatal alliance between Christian faith and cultural experience.

He began working through the problems posed by the war and the failure of liberal theology to account for such a dark episode in human history. He initiated a radical change in theology, stressing the "wholly otherness of God" over the anthropocentrism of 19th-century liberal theology. He questioned the liberal theology of his German teachers and its dependence on the rationalist, historicist, and dualist thought that stemmed from the Enlightenment. Barth believed that liberal theology had accommodated Christianity to modern culture, and it had to be changed.

Being aware that the theology which he had been taught gave him little to say to his congregation, Barth reviewed his philosophy and theology. Thus started a period of theological study, particularly of the Bible. He discovered in the Bible a "strange new world": the Bible was not about our religion or morality or history, but about the Kingdom of God. This biblical reality can be understood only by inhabiting it.

In 1916 Barth began a careful study of Paul's Letter to the Romans. The result of these efforts was his first major work, The Epistle to the Romans (First published in 1919 and then completely rewritten in 1922.), in which he contradicted the liberal theologians who considered Scripture little more than an account of human religious experience and who were concerned only with the historic personality of Christ. According to Paul, argues Barth, God condemns all human undertakings and saves only those people who trust not in themselves but solely in God. Barth argued that in Scripture we find "divine thoughts about men, not human thoughts about God." God is God and he has wrought our salvation.

Romans is a huge, breathless, exciting sermon rather than commentary. In it Barth reflect on what he would later call "the Godness of God." What God thinks about people is more important than what they thing about God. Human knowledge can lead us to a void, a longing and a dissatisfaction. God, the living God, had come to deliver confused, self-contradictory human beings like himself from their sin. In this book Barth stressed the discontinuity between the Christian message and the world. God is the wholly other, and known only in revelation. Human task is to reshape himself or herself to God's design, rather than the other way around.

This study brought him to the attention of theologians everywhere. The book divided the theological world of Germany and Switzerland into advocates and bitter detractors. This book initiated the revival of orthodox Protestantism based on the Bible. There were numerous younger theologians who saw in Barth's Romans an expression of their own theological program. Among those were Emil Brunner, Bultmann, George Merz and Friedrich Gogarten. In the fall of 1922, Barth, Thurneysen, Gogarten, and Merz started a journal entitled Zwischen den Zeiten (Between the Times) which was to be the organ of the new "theology of crisis". This journal played an important role in shaping German theology for the next decade, until it was discontinued in 1933.

The main characteristic of Barth's work, known as neoorthodoxy and crisis theology, is on the sinfulness of humanity, God's absolute transcendence, and the human inability to know God except through revelation. The critical nature of his theology came to be known as "dialectical theology," or "the theology of crisis". This initiated a trend toward neoorthodoxy in Protestant theology. The neoorthodoxy of Karl Barth reacted strongly against liberal Protestant neglect of historical revelation. He wanted to lead theology away from the influence of modern religious philosophy, with its emphasis on feeling and humanism, and back to the principles of the Reformation and the teachings of the Bible. He viewed the Bible, however, not as the actual revelation of God but as only the record of that revelation. God's single revelation occurred in Jesus Christ. In short, Barth rejected two main lines of interest in Protestant theology of that time: historical criticism of the Bible and attempt to find justification for religious experience from philosophy and other sources. Barth saw in historical criticism great value on its own level, but it often led Christians to lessen the significance of the testimony of the apostolic community to Jesus as being based on faith and not on history. Theology which uses philosophy is always on the defensive and more anxious to accommodate the Christian faith to others than to pay attention to what the Bible really says.

On the basis of the publication of Romans (he had never earned a doctorate), Barth was appointed professor at the universities of Göttingen, Münster, and Bonn, successively. In Göttingen he did an exhaustive study of the great Protestant scholastic theologians. In 1927 he wrote his first attempt at dogmatics, The Doctrine of the Word of God: Prolegomena to Church Dogmatics, in which he addressed the Word of God, divine revelation, the Trinity, Incarnation, and the Holy Spirit. It turned out to be a "false start." His engagement with epistemological issues made him dissatisfied with what he had done. He became aware that he was still working within a liberal, anthropocentric framework. When he moved to Bonn he war forced to rethink his whole theological method in order to avoid grounding his theology in an existential anthropology. His theology represented a significant break with his earlier dialectical thinking. In 1931 he produced his celebrated study of St. Anselm, Fides quaerens intellectum.

In the following year he published the first part of his Church Dogmatics. During this time Barth also wrote several small commentaries, expositions of the Apostles' Creed, and the Heidelberg and Geneva catechisms.

Barth was not only Protestantism's preeminent theologian, but a public figure. With the rise of Adolf Hitler to power in 1933, Barth emerged as a leader of the church opposition, expressed in the Barmen Declaration of 1934. In April of 1933 the "Evangelical Church of the German Nation" was created and published the following guiding principles: "We see in race, folk and nation, orders of existence granted and entrusted to us by God. God's law for us is that we look to the preservation of these orders....In the mission to the Jews we perceive a grave danger to our nationality. It is the entrance gate for alien blood into our body politic....In particular, marriage between Germans and Jews is to be forbidden. We want an evangelical Church that is rooted in our nationhood." (Cited in Arthur C. Cochrane, The Church's Confession Under Hitler. Philadelphia, 1962, pp. 222-223)

Barth was one of the founders of the so-called Confessing church, which rejected Nazi nationalist ideology of "blood and soil" and the attempt to set up a "German Christian" church. In May of 1934 representatives of the Confessing church met at Barmen and out of that meeting came the Barmen Declaration, largely based on a draft that Barth had prepared. It expressed his conviction that the only way to resist the collapse of the church in Nazi Germany was to hold fast to true Christian doctrine, i.e., to affirm the sovereignty of the Word of God in Christ over against all idolatrous political ideologies. "Jesus Christ, as he is attested to us in Holy Scripture, is the one Word of God whom we have to hear, and whom we have to trust and obey in life and in death. We reject the false doctrine that the church could and should recognize as a source of its proclamation, beyond and besides this one Word of God, yet other events, powers, historic figures, and truths as God's revelation… We reject the false doctrine that there could be areas of our life in which we would belong not to Jesus Christ but to other lords, areas in which we would not need justification and sanctification through him."

Barth refused to take the oath of unconditional allegiance to Hitler which cost him his chair in Bonn in 1935. Barth's refusal to comply with an instruction by the rector of the University of Bonn to end each lecture with the German salute put a provisional end to Barth's professional career in Germany. Barth himself described why he refused to comply: "I have begun my lecture (in summer at seven o'clock, in winter at eight o'clock) for the past two and one-half years with a brief devotion consisting of the reading of two Bible verses and the singing of two or three verses of a hymn by all present. The introduction of the Hitler salute in this context would be out of place and diversionary." (Prolingheuer, Der Fall Karl Barth, 240: Letter to Rust 16 December 1933).

He returned to his native Basel where he remained until his death, December 10, 1968 at the age of 82. He continued to champion the cause of the Confessing Church, of the Jews, until the end of the war. After the war, Barth was invited back to Bonn, where he delivered the series of lectures published in 1947 as Dogmatics in Outline. He spoke at the opening meeting of the Conference of the World Council of Churches in Amsterdam in 1948. Following the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), he visited Rome, a visit of which he wrote in Ad limina apostolorum. He was regular visitor to the prison in Basel (Deliverance to the Captives, 1959).

From 1932 to 1967 he worked on his Church Dogmatics, a multivolume work that was unfinished at his death. It consists of 13 parts in four volumes, running altogether to more than 9,000 pages. Although he changed some of his early positions, he continued to maintain that the task of theology is to unfold the revealed word attested in the Bible, and that there is no place for natural theology or the influence of non-Christian religions. His theology depended on a distinction between the Word (i.e., God's self-revelation as concretely manifested in Christ) and religion. Religion, according to Barth, is human attempt to grasp at God and is opposed to revelation, in which God has come to humans through Christ. "Religion is the enemy of faith." "Religion is human's attempt to enter into communion with God on his own terms."