Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images & Physiognomic Interpretation

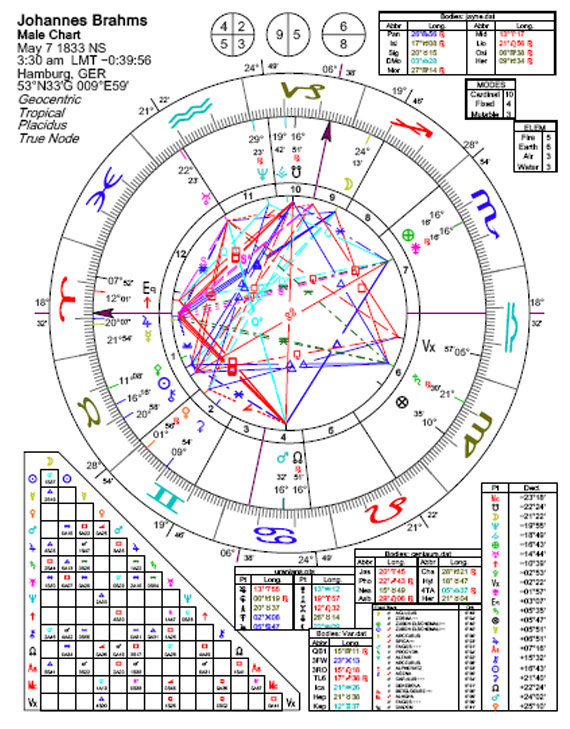

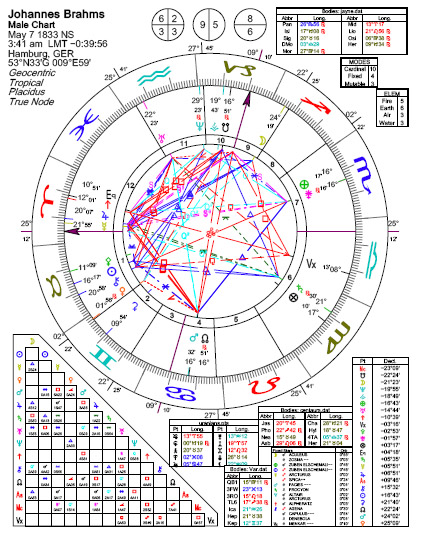

Johannes Brahms—German Composer: May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany, 3:30 AM, LMT (Source: Kraum) Additional sources give 3:40 AM and 3:41 AM.

“Barbault quotes Hans Ritter for an old parochial register. Kraum gave the same data in “Astrol Rundschau,” NAJ, 7/1935. Lyndoe had 3:40 AM in AA, 1/1968. Robert Jansky had 4:00 PM. Sabian Symbols No.124 has 3:41 AM.(Proposed Ascendant, Aries with Pluto in Aries near the Ascendant and Jupiter conjunct Mercury in Aries, also near the Ascendant; Moon in Sagittarius in H9; Venus retrograde in Gemini; Mars in Cancer; Saturn in Virgo H6; Uranus in Aquarius; Neptune in the last degree of Capricorn)

Johannes Brahms was one of the world’s great composers, and with Bach and Beethoven, is remembered as one of the “three B’s” of Germany. These composers represented the fourth ray soul of that nation, and all of them, were, so the author proposes, focussed upon the fourth ray in their soul. All, as well, had, it would seem, a strong first ray in their personality. Brahms knew his Bible well—his Sagittarius Moon and Virgoan Saturn contributing to the strength of the sixth ray to be found in his nature, evidenced as well by his life-long devotion to Clara Schumann, the wife of his teacher and mentor, romantic composer, Robert Schumann, and by his strong and exalted religious feeling pouring through his sacred music.

The rich harmonies of Brahms’ music, and its thick textures, can be attributed in part to the Taurean influence in his chart. His romantic classicism, (so different from the unrestrained romanticism of Wagner—who hated the music of Brahms) is furthered by form-conscious Saturn in exacting Virgo (the same sign position for Saturn as in Bach’s chart). His Saturn is very powerful, trining his Taurus Sun and squaring his inspirational Moon in Sagittarius. Brahms, however disorderly or gruff he may have been in his personal life, was a patient craftsman in relation to his music. His exacting, discriminating quality is reinforced by the Saturn in Virgo, H6, position (both Virgo and the sixth house relating to disciplined labor)

His fertility of thought is partially attributable to Jupiter conjunct Mercury in Aries, the esoteric ruler of the Ascendant. ?is conjunction is, as well, trine the ninth house Moon, giving the urge expand freely and joyously. Saturn in Virgo however, not only squares the Moon but trines Jupiter/Mercury, adding a characteristic restraint to much of Brahms’ music. ?e Saturn is further strengthened by being the focal point of a Yod, with the other points being Uranus, Mercury. He channeled his considerable originality and his many musical ideas through the severity of this Saturnian taskmaster. It is signi?cant that although he wrote instrumental music of every variety, and many “lieder” or songs, he never wrote opera. Perhaps his powerfully aspected Saturn, and his brooding Pluto (in its own esoteric sign and house), as well as his inwardly turbulent but internalized Mars in Cancer (the sign of its fall), inclined him too much towards introversion to indulge in so emotionally exuberant an art form as opera.

Aries, holding three planets, and coloring the Ascendant, gives the theme of resurrection (so prominent in his Deutches Requiem—German Requiem), and the bursts of freedom which rise suddenly from the Taurean ray-one ‘brooding’ of much of his music. Something of this joy can be heard in the Academic Festival Overture, correlating with his freedom-loving Sagittarian Moon in the house of higher education. He played a great joke on the serious, academic music-lovers who commissioned the work, by taking a famous student drinking song as the major melodic theme. He had the reputation (among those who knew him) for being a humorous man. In entirely different vein, it can be said that Brahms was haunted by the spectre of death (Pluto conjunct the Aries Ascendant from H12), but he perpetually overcame this SAness and foreboding with the resurrective energy of Aries in which Jupiter is rising. His Four Serious Songs are a testimonial to the power of Love (Jupiter) over death (Pluto).

Brahms ray four soul has strong entry points through the Sagittarius Moon (Sagittarius distributes ray four as does the Moon—in its own special way), and through ray four Taurus (and its rulers), the Sun Sign which so powerfully conditioned Brahms. Venus, orthodox ruler of Taurus in versatile Gemini, contributed to the different forms through which Brahms expressed—many, really, compared to Wagner who focussed entirely on opera—the one medium Brahms did not touch.

The sixth ray is strengthened by two signs—Virgo and Sagittarius, holding Saturn and the Moon, respectively. Brahms knew his Bible very well; as the Saturn/Moon square from Virgo to Sagittarius indicates. Sixth ray Mars in Cancer (a sign correlated to the solar plexus) and in the fourth house of heredity and the past, shows a deeply emotional and creative unrest stirring within his psyche.

As for the First ray, his probable personality ray, there is much of Vulcan (the esoteric ruler of the Sun Sign) in Brahms. Taurus is powerful and, given the position of the Sun in the middle of the sign, certainly found in its own sign, Taurus.

Brahms was a deeply religious, spiritual man—an inspired man. In a rare interview granted just months before he died he revealed his relation to the soul, to the divine, to inspiration—and requested that the content of this interview not be published for fifty years. He feared that if people understood his approach to the soul they would not listen to his music. This was the conservative Taurus/Virgo energy speaking.

In fact, Brahms was a composer of the heart—another of the great German composers with access to the buddhic plane (the plane correlating to the fourth ray soul of Germany). Though much of his music may seem melancholy, in his soul he was not. The music of Brahms at his best, melts the heart—the power of buddhi—expressed through the close trine between an elevated and compassionate Neptune, and Venus, the planet of beauty in the second ray sign, Gemini.

Brahms on Bruckner (and Wanger debate) The best ideas come to me when I polish my shoes early in the morning.

When I feel the urge to compose, I begin by appealing directly to my Maker and I first ask Him the three most important questions pertaining to our life here in this world—whence, wherefore, whither.

[Of some of his late piano music] “Even one listener is too many … and that includes the performer.

I once told Wagner himself that I was the best Wagnerian of our time.

QUOTES ON BRAHMS

I felt … that one day there must suddenly emerge the one who would be chosen to express the most exalted spirit of the times in an ideal manner, one who would not bring us mastery in gradual developmental stages but who, like Minerva, would spring fully armed from the head of Jove. And he has arrived - a youth at whose cradle the graces and heroes of old stood guard. His name is Johannes Brahms.[Of Brahms’ piano sonatas] Veiled symphonies. - Robert Schumann

I believe Johannes to be the true Apostle, who will also write Revelations. - Robert Schumann (Letter to Joseph Joachim)

[Of Brahms’ German Requiem] “Schumann’s Last Thought.” - Richard Wagner

For the drawing room he is not graceful enough, for the concert hall not fiery enough; for the countryside he is not primitive enough, for the city not cultured enough. I have but little faith in such natures. - Anton Rubinstein (Letter to Franz Liszt)

In newspaper column Eduard Hanslick once quipped about Brahms, who had sprouted a beard during his summer vacation, saying that his original face was just as hard to recognize as the theme in many of his variations. (Hans Gall, Johannes Brahms, 1961)

[Of Brahms] “I know of some famous composers who in their concert masquerades choose the disguise of a cabaret singer one day [Liebeslieder waltzes], the hallelujah periwig of Handel the next [Song of Triumph], the dress of a Jewish csárdlis fiddler another time [Hungarian Dances], and then again the guise of a highly respectable symphonic composer dressed up as a Number Ten [Hans von Bülow had described Brahms’ First Symphony as Beethoven’s Tenth].” - Richard Wagner (Wagner, ‘On Poetry and Composition)

[Referring to Brahms] “The evil only starts when one attempts to compose better than one can.” - Richard Wagner (Wagner had just quoted Mendelssohn's comment on Berlioz: “Everybody composes as well as he can.”; Wagner

“I have played over the music of that soundrel Brahms. What a guiltless bastard!” - Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky- (Diary, 1886)

“Brahms’ Tragic Overture brings to mind the entry of a ghost in a Shakespearean drama, startling the murderer by its presence but invisible to all others. We do not know whom Brahms has murdered in his Tragic Overture.” - Hugo Wolf (Lebrecht, Discord, 1982)

“Brahms’ Requiem has not the true funeral relish: it is so execrably and ponderously dull that the very flattest of funerals would seem like a ballet, or at least a danse macabre, after it. - George Bernard Shaw

“His Requiem is patiently borne only by the corpse.” - George Bernard Shaw

The real Brahms is nothing more than a sentimental voluptuary … rather tiresomely addicted to dressing himself up as Handel or Beethoven and making a prolonged and intolerable noise.” - George Bernard Shaw

Too much beer and beard” - Paul Dukas

“A landscape, torn by mists and clouds, in which I can see ruins of old churches, as well as of Greek temples - that is Brahms.” - Edvard Grieg (Letter to Henry T. Finck, 1900)

Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms was born in Hamburg. His father, Johann Jakob Brahms, came to Hamburg from Schleswig-Holstein seeking a career as a town musician. He was proficient on several instruments but found employment mostly as a horn player and double bassist. He married Christiane Nissen, a seamstress, who was considerably older than he was. They lived in the poor Gängeviertel district of the city, near the docks.Johann Jakob gave his son his first musical training. He studied piano from the age of 3. Brahms showed early promise on the piano (his younger brother Fritz also became a pianist) and helped to supplement the rather meager family income by playing the piano in restaurants and theaters, as well as by teaching. It is a long-told tale that Brahms was forced in his early teens to play the piano in bars that doubled as brothels; recently Brahms scholar Kurt Hoffman has suggested that this legend is false. Since Brahms himself clearly originated the story, however, some have questioned Hoffman's theory.

For a time, Brahms also learned the cello, although his progress was cut short when his teacher absconded with Brahms's instrument. His piano teachers were first Otto Cossel and then Eduard Marxsen, who had studied in Vienna with Ignaz Seyfried (a pupil of Mozart) and Carl von Bocklet (a close friend of Schubert). The young Brahms gave a few public concerts in Hamburg, and though he did not become well known as a pianist he made some concert tours in the 1850s and 60s and in later life frequently participated in the performance of his own works, whether as soloist, accompanist, or participant in chamber music. Notably he gave the premieres of both his Piano Concerto No. 1 in 1859 and his Piano Concerto No. 2 in 1881. In his early teens he began to conduct choirs and eventually became an efficient choral and orchestral conductor.

He began to compose quite early in life (we know of a piano sonata he played or improvised at the age of 11), but his efforts did not receive much attention until he went on a concert tour as accompanist to the Hungarian violinist Eduard Reményi in April-May 1853. On this tour he met Joseph Joachim at Hanover, and went on to the Court of Weimar where he met Franz Liszt, Cornelius and Raff. According to several witnesses of Brahms's meeting with Liszt (at which Liszt performed Brahms's own op.4 Scherzo at sight), Reményi was offended by Brahms' failure to praise Liszt's Sonata in B minor wholeheartedly (Brahms fell asleep during a performance of the recently-composed work), and they parted company shortly afterwards, although it was not clear as to whether Liszt felt offended or otherwise.

Joachim had given Brahms a letter of introduction to Robert Schumann, however, and Brahms walked to Düsseldorf, arriving on 30 September and being welcomed into the Schumann family. Schumann, amazed by the 20-year-old's talent, published an article 'Neue Bahnen' (New Paths) in the journal Neue Zeitschrift fur Musik alerting the public to the young man whom he claimed was 'destined to give ideal expression to the times'. This pronouncement was received with some scepticism outside Schumann's immediate circle, and may have increased the naturally self-critical Brahms's need to perfect his works and technique. While he was in Düsseldorf Brahms participated with Schumann and Albert Dietrich in writing the jointly-composed 'F-A-E' Sonata for Joachim. He became very attached to Schumann's wife, the composer and pianist Clara, 14 years his senior, with whom he would carry on a lifelong, emotionally passionate, but perhaps only platonic, relationship. Brahms never married, despite strong feelings for several women and despite entering into an engagement, soon broken off, with Agathe von Siebold in Göttingen in 1859. After Schumann's attempted suicide and subsequent incarceration in a mental sanatorium near Bonn in February 1854, Brahms was the main go-between between Clara and her husband, and found himself virtually head of the household.

Brahms' grave in the Zentralfriedhof (Central Cemetery), Vienna.After Schumann’s death at the sanatorium in 1856 Brahms divided his time between Hamburg, where he formed and conducted a ladies’ choir, and the principality of Detmold, where he was court music-teacher and conductor. He first visited Vienna in 1862, staying there over the winter, and in 1863 was appointed conductor of the Vienna Singakademie. Though he resigned the position the following year he based himself increasingly in Vienna and soon made his home there, though he toyed with the idea of taking up conducting posts elsewhere. From 1872 to 1875 he was Director of the concerts of the Vienna Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde; afterwards he accepted no formal position. He refused an Honorary Doctorate of Music from University of Cambridge in 1877 (he was afraid of being lionized in England, where his music was already very popular) but accepted one from the University of Breslau in 1879, composing the Academic Festival Overture in response.

He had been composing steadily throughout the 1850s and 60s, but his music had evoked divided critical responses and the First Piano Concerto had been badly received in some of its early performances. His works were labelled old-fashioned by the 'New German School' whose principal figures included Liszt and Wagner. Brahms in fact admired some of Wagner's music and admired Liszt as a great pianist, but in 1860 he attempted to organize a public protest against some of the wilder excesses of their music. His manifesto, which was published prematurely with only three supporting signatures, was a ludicrous failure and he never engaged in public polemics again. It was the premiere of Ein deutsches Requiem, his largest choral work, in Bremen in 1868 that confirmed Brahms's European reputation and led many to accept that he had fulfilled Schumann’s prophecy. This may have given him the confidence finally to complete a number of works that had been wrestled with over many years, such as the cantata Rinaldo, his first String Quartet, Third Piano Quartet and, most notably, his First Symphony; this appeared in 1876, though it had been begun (and a version of the first movement seen by some of his friends) in the early 1860s. The other three symphonies then followed in fairly rapid succession (1877, 1883, and 1885). From 1881 he was able to try out his new orchestral works with the court orchestra of the Duke of Meiningen, whose conductor was Hans von Bulow.

Brahms frequently traveled, for both business (concert tours) and pleasure. From 1878 onwards he often visited Italy in the springtime, and usually sought out a pleasant rural location in which to compose during the summer. He was a great walker and especially enjoyed spending time in the open air, where he felt that he could think more clearly.

In 1890, the 57-year-old Brahms resolved to give up composing. However, as it turned out, he was unable to abide by his decision, and in the years before his death he produced a number of acknowledged masterpieces. His admiration for Richard Muhlfeld, clarinettist with the Meiningen orchestra, caused him to compose the clarinet quintet Op.115 (1891), clarinet trio Op.114 (1891) and the two clarinet sonatas Op. 120 (1894). He also wrote several cycles of piano pieces, Opp.116-119 and the Four Serious Songs (Vier ernste Gesänge) Op. 121 (1896).

While completing the Op. 121 songs Brahms fell ill of cancer (sources differ on whether this was of the liver or pancreas). His condition gradually worsened and he died on April 3, 1897. Brahms is buried in the Zentralfriedhof in Vienna.

Although Brahms may be often regarded as one of the last bastions of the Romantic Period, he was not a mainstream Romantic but rather maintained a Classical sense of form and logic within his works in contrast to the opulence and excesses of many of his contemporaries. Thus many admirers--though not necessarily Brahms himself---saw him as the champion of traditional forms and "pure music," as opposed to the New German embrace of program music. Alongside Anton Bruckner, Brahms was perhaps the major practitioner of the symphony during the latter half of the 19th century; his symphonies helped revive a virtually moribund genre and pave the way for others such as Gustav Mahler and Jean Sibelius. Though he was viewed as diametrically opposed to Wagner during his lifetime, it is incorrect to characterize Brahms as a reactionary. His point of view looked both backward and forward; his output was often bold in harmony and expression, prompting Arnold Schoenberg to write his important essay entitled "Brahms the Progressive" which paved the way for the revaluation of Brahms's reputation in the 20th century. Only in recent decades have scholars begun to examine Brahms's remarkably original rhythmic conceptions, which include 5- and 7-beat meters.

It is (perhaps) significant that Brahms himself had considered giving up composition at a time when all notions of tonality were being stretched to their limit and that further expansion would seemingly only result in the rules of tonality being broken altogether. It should be noted, however, that he offered substantial encouragement to Schoenberg's teacher Alexander Zemlinsky and was apparently much impressed by an early quartet of Schoenberg's.

Brahms's personality

Like Beethoven, Brahms was fond of nature and often went walking in the woods around Vienna. He often brought penny candy with him to hand out to children. To adults Brahms was often brusque and sarcastic, and he sometimes alienated other people. His pupil Gustav Jenner wrote, "Brahms has acquired, not without reason, the reputation for being a grump, even though few could also be as lovable as he.[1]" He also had predictable habits which were noted by the Viennese press such as his daily visit to his favourite 'Red Hedgehog' tavern in Vienna and the press also particularly took into account his style of walking with his hands firmly behind his back complete with a caricature of him in this pose walking alongside a red hedgehog. Those who remained his friends were very loyal to him, however, and he reciprocated in return with equal loyalty and generosity. He was a lifelong friend with Johann Strauss II though they were very different as composers. Brahms even struggled to get to the Theater an der Wien in Vienna for Strauss' premiere of the operetta Die Göttin der Vernunft in 1897 before his death. Perhaps the greatest tribute that Brahms could pay to Strauss was his remark that he would have given anything to have written The Blue Danube waltz. An anecdote dating around the time Brahms became acquainted with Strauss is that the former cheekily inscribed the words 'alas, not by Brahms!' on a fan decorated with the theme of the famous 'Blue Danube' waltz.Starting in the 1860s, when his works sold widely, Brahms was financially quite successful. He preferred a modest life style, however, living in a simple three-room apartment with a housekeeper. He gave away much of his money to relatives, and anonymously helped support a number of young musicians.

Brahms was an extreme perfectionist. We know he destroyed many early works, including a Violin Sonata he performed with Reményi and the great violinist Ferdinand David. He claimed once to have destroyed 20 string quartets before he issued his official First in 1873. The First Piano Concerto was evolved over several years out of an original project for a Symphony in D minor, and the official First Symphony was toiled over from about 1861 to 1876. Even after its first few performances, Brahms destroyed the original slow movement and substituted another before the score was published. (A conjectural restoration of the original slow movement has been published by Robert Pascall.) Another factor that contributed to Brahms's perfectionism was that Schumann had announced early on that Brahms was to become the next great composer like Beethoven, a prediction that Brahms was determined to live up to. This prediction hardly added to the composer's self-confidence, and may have contributed to the delay in producing the First Symphony. However, Clara Schumann noted before that Brahms' First Symphony was a product that was not reflective of Brahms' real nature as she felt that the final exuberant movement was 'too brilliant' as she was encouraged by the dark and tempestuous opening movement when Brahms first sent to her the initial draft. However, she recanted in accepting the Second Symphony, which has often been seen in modern times as one of his sunniest works. Other contemporaries, however, found the first movement especially dark, and Reinhold Brinkmann, in a study of Symphony No.2 in relation to 19th-century ideas of melancholy, has published a revealing letter from Brahms to the composer and conductor Vinzenz Lachner in which Brahms confesses to the melancholic side of his nature and comments on specific features of the movement that reflect this.

As for Brahms's place in musical history, which so concerned him, he would no doubt be gratified in knowing that posterity has indeed placed him among the three great "Bs" of German composers — Bach, Beethoven and Brahms.

Jeffery Dane shares insights in the life of Johannes Brahms, who "accomplished more in a single year than most others do in their own lifetimes." He was responsible for some of the greatest musical pieces ever written, yet was a modest man. He refused to sail in a ship or pay taxes on his tobacco (he was once caught attempting to smuggle some through customs). A fascinating character!

by Jeffrey Dane

© Jeffrey Dane 2001When asked to fill out a biographical form, one modest man wrote, "Happily impossible, I would have to paint nothing but zeros and dashes in these columns. I have had no experiences that I could communicate. I have attended no schools or institutions for musical culture. I have embarked on no travels for purposes of study. I have received no instruction from eminent masters. I am the incumbent of no public offices, and I hold no official positions. Well, then, what am I to write here?" - Johannes Brahms.

Another quote attributed to him is a near-perfect illustration of the stoicism and self-confidence that stood him in such good stead throughout his life - and is something from which many of us could learn and benefit even now. It also seems to encapsulate in a mere seventy words an idea that's occurred to most of us, and it proves that some of the nonsense we see in contemporary society today is not a modern phenomenon, but an eternal verity prevalent even in Brahms' day. "Those who enjoy their own emotionally bad health and who habitually fill their own minds with the rank poisons of suspicion, jealousy and hatred, as a rule take umbrage at those who refuse to do likewise, and they find a perverted relief in trying to denigrate them. A pity. In so doing, such unfortunates are deceiving no self-thinking person, for they reveal much about themselves and little about their targets."

When we think of Johannes Brahms we tend to envision a tall, portly, kindly, grandfatherly man writing cradle songs, with long hair down to his shoulders, and a long grey beard. Actually, he was relatively short (like Beethoven), and he became rather rotund later in life. He had a great, benevolent heart which he sometimes had to conceal behind a sometimes abrupt but protective exterior. He had no children. He wore his hair long, unfashionable in his day - and his great beard effectively defines him in his photos.

We usually see only the proverbial tip of the iceberg. As there's more to Leonardo da Vinci than his Mona Lisa and more to Jules Verne than his "Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea," there's more to Brahms than just his "Lullaby"--by title and tune one of the world's most recognizable pieces. It was originally composed as a song for voice and piano, and titled Wiegenlied (pronounced VEE-gen-leed, meaning "cradle-song"), with a dedication to Bertha Faber. Bertha Porubszky was a singer and a friend of Brahms' from his days in Hamburg. After she married the industrialist Arthur Faber of Vienna, Brahms commemorated the birth of her first child with his most famous piece.

His character is one of the most fascinating in the entire history of music, and his nature one of the most noble. He sometimes spoke and wrote his letters as though he were actually trying to conceal his meaning rather than clarify it.

Some, especially his adversaries, saw only a formidable stubbornness in Brahms the Conservative, while others recognized the unyielding integrity of Brahms the Classicist. Both views had merit. In some ways he was a real idealist and in others an ideal realist, at times very pragmatic. Hidden behind his sometimes bearish façade was a real restraint and true unpretentiousness belying the outward gruffness (usually directed only at the privileged), a deep-rooted generosity which often benefited others (especially needy children) - and a heart big enough for Clara Schumann to live in.

* * * * * * * * *

His lifelong personal friendship and occasional professional collaboration with pianist Clara Schumann paralleled the later personal friendship and professional collaborations between Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy, "the actor's actor." Tracy himself found Brahms' personality so engaging that he considered portraying him in a film biography of the composer, provided he could grow his own beard for the role. Interestingly, Hepburn had portrayed Clara Schumann in the 1947 film, "Song of Love," in which she appeared with Paul Henreid (Robert Schumann) and Robert Walker (the young Brahms).

Clara Schumann's significance in Brahms' life can't be understated - or, by some, even understood. Fourteen years older than him and in her prime, she entered his life when he was 20, blond, blue eyed and boyish-looking. The attraction, which was mutual, is easy to understand. She, the great pianist, worshiped her husband Robert, the great composer. The young Brahms worshiped both of them. They also adored him, especially Clara, who saw him first as a son, then as a friend. A remarkable and extraordinarily gifted woman in her own right, she was an altogether unique phenomenon in his life. Her death in 1896 left an unfillable void in his existence. She was gone but surely not lost, for his memory of her may have consoled him for no longer being young. In a very real sense, they spent their lives with each other: though not side by side, they were surely together.

He never married. Some have noticed a correlation between Brahms' lifelong attraction to Clara Schumann and the fact that his own mother, to whom he was devoted and largely in whose memory his Requiem was composed, was 17 years older than his father.

Their interaction was as deep as Clara's relationship with her own husband, nine years her senior and with whom she had eight children: Marie (1841), Elise (1843), Julie (1845), Emil (1846), Ludwig (1848), Ferdinand (1849), Eugenie (1851) and Felix (1854). Schumann never saw his last child, born only after he had been institutionalized. In her memoirs, their daughter Eugenie, a trained observer, gave a significant account not only of her family's life but also of Brahms' piano-playing. His hands were large - not disproportionately so but unusually so - which may help explain the stretches, leaps, and plethora of notes in some of his piano music. His playing in his youth was described as noble, musicianly, and often inspired.

Brahms could be very candid. When Clara proposed writing a biography of her famous husband, Brahms wrote to her, in 1856, "What would become of all historical research and all biographies if they were always written with consideration for people's feelings? Such a biography as you, for example, would write about your Robert would surely be very beautiful to read, but would it as surely be of historical value?" Observations as penetrating as these bespeak a maturity unusual in a 23-year-old - but we must remember who we're dealing with here. Clara herself wrote in her diary about him, very soon after they met: "He is so masterful that it seems God sent him into the world complete."

The image of discretion in each other's company, they shared a tender yet intense personal interaction throughout their lives. The bond between the young Brahms and the Schumanns was cemented while he lived in their home at Bilkerstrasse 15 in Düsseldorf, but the personal connection between him and Clara was as singular for both of them as was the nature of her own 16-year marriage, which ended only with her husband's death in the asylum at Endenich, near Bonn, on July 29, 1856.

In a Romantic age, she was a classical performer who worked with the great artists of her day. Brahms was a creator, some of whose works are, effectively, portraits of her. For nearly half a century their friendship was almost unique in the annals of human interaction. The depth of their relationship stands on its own and needs no dramatic embellishment a-la-Hollywood. They blessed posterity with their individual contributions - and robbed it by leaving no photographs of the two of them together.

"It is obvious that we who go on living must see many things vanish with the years - things with which it is more difficult to part than with years of life. . . No-one can be more attached or devoted to you than I am." Thus he wrote to his beloved friend on the untimely death of her young and stunningly beautiful daughter, Julie (whose marriage had inspired the creation of his Alto Rhapsody for soloist, chorus and orchestra).

It's conceivable the very special friendship between Brahms and Clara Schumann may have contributed in some measure to the psychological deterioration of her husband, notwithstanding the known history of mental instability in his family. What she meant to her younger friend must have been very clear to his intimates - as clear, perhaps, as the tears that might have filled his eyes when Brahms thought of her during the last days of his life. "When those dear eyes are closed, so much will have ended for me," he wrote during her final illness.

He ultimately destroyed many of her letters for the same reason he did away with early sketches and studies for his own work. Many of his missives to her have survived, allowing us only a partial and imbalanced view of their correspondence - if not actually "equivalent" then certainly comparable to eavesdropping on his end of phone conversations with her.

It seems as incontrovertible as the Pythagorean theorems that Johannes Brahms and Clara Schumann each shared an extra life, and that they were as alive then as we are today.

* * * * * * * * *

In accordance with his personal tastes and character, Brahms lived a relatively uneventful life, compared with those of the most famous actors and diplomats of his day, or even some of the most celebrated musicians. We don't remember most of them. We remember him. His daily routine in Vienna was fairly consistent and is a matter of record. Rising early, he'd brew his strong black coffee and enjoy it with some sweet rolls. After this simple but satisfying breakfast, he'd compose throughout the morning and sometimes into the afternoon. As did Beethoven, Brahms would take long afternoon walks around Vienna, one of his favorite places being the Prater, a large park still drawing visitors, and the site of Vienna's now world-famous Ferris wheel, the Riesenrad (built only within a year or two after Brahms' death). He worked little in the evenings, preferring to spend time with friends, dining, having a beer or two, or playing cards with cronies in the unpretentious second-floor dining room at his favorite restaurant, Zum Roten Igel (The Red Hedgehog), which no longer exists. Paradoxically, the building where he lived for the last 26 years of his life was demolished unceremoniously exactly ten years to the date after he died there. The structure now on that site is a wing of the city's Technical University.

Brahms was always generous to others, and devoted to his own family. Preparing to leave for Vienna, he wrote to his father, who was also a musician, "If things ever go badly with you, bear in mind that music is always the best consolation. Just read industriously in my old copy of Saul, and there you will find what you need." Not long afterward, Johann Jakob Brahms remembered the advice. When he turned for spiritual comfort to his son's tattered score of Handel's oratorio, he was elated to find that his son had left the pages liberally interleaved with banknotes.

He had a younger sister, Elise, and a younger brother, Fritz (Friedrich), who became a fashionable piano teacher in Hamburg - but whose disposition was not improved by his nickname, The Wrong Brahms.

He also put pressure on his own publisher, Simrock of Berlin, to bring out the music of a still-struggling young Czechoslovakian composer. Brahms didn't suffer fools lightly but he could be very considerate and magnanimous when he saw genuine talent and skill. He held this younger man and his music in very high regard, and when the younger composer wrote his own Cello Concerto, Brahms was almost suicidal, wishing that he, himself, had composed it. From one composer to another there can be few finer compliments, and that this sentiment came from the man who was, musically, the primary classical European figure spoke volumes. The young Czech composer of whom Brahms thought so highly was Antonin Dvorak.

While on a holiday, Brahms' gold pocketwatch was stolen one day from his rooms, which he had never locked. When he was urged to take the matter up officially with the police, he's said to have dismissed the notion with the remark, "Leave me in peace. The watch was probably carried off by some poor devil who needs it more than I do."

He was very particular about his journeys. His one youthful seagoing experience (in a skiff) caused a life-long hatred even of the prospect of travel on water. He once arranged to sail from Genoa to Sicily with three friends, but already on the gangplank he suddenly "jumped ship" and opted for the lengthy, tiring railway journey to Reggio, in sight of Messina.

His practical sense of reasoning prompted him to see questionable or unpleasant situations from a disarmingly rational viewpoint: "I see no reason why I should subject myself to such discomfort." The stance cost him an honorary doctorate from Cambridge in England, whose offer in 1877 had been conditioned on its being accepted in person - which would have involved his having to cross the English Channel. While Beethoven had a fascination with England, Brahms had an indifference to it. He even asked his publisher to print certain editions of his songs - ultimately more than 250 of them - without the English words.

The loss of the doctorate was tempered by a degree offered him two years later by the University of Breslau. He thanked them, of course - a year afterward, with a postcard, the advent of which as a time-saver Brahms proclaimed as a godsend. Informed by a colleague that his personal presence would be "appreciated" at the ceremonies, he gladly agreed to accept the honor in person, since it didn't involve boat travel. His piece, the Academic Festival Overture, was composed especially for the occasion and included medleys of student songs (including Gaudeamus Igitur). The first performance was given at the ceremonies, and the piece is scored for the largest orchestra for which Brahms ever wrote.

A practical man, his choice of holiday destinations depended upon the ease and convenience of railroad schedules and train connections. When traveling, in a train compartment Brahms would considerately ask a lady's permission to smoke. When entering a Catholic church, observant of protocol he would pretend, with his Protestant hand, to take holy water. In hotels he would place his shoes in the corridor in the early evening, and go about stocking-footed ". . .so as not to shorten the sleep of some poor servant."

* * * * * * * * *

Like his personal nature, Brahms' religious view was unconventional and idiosyncratic. His attitude challenged dogma and therefore threatened the comfort and even the security of those who subscribed to doctrine. It was essentially a reflection of his love of life rather than a conventional religious fear of death and redemption through suffering. He celebrated this in his German Requiem (so titled because the text is sung in German rather than Latin) by omitting the traditional Dies Irae (Days of Wrath) section, which Brahms felt would be inconsistent with his concept.

The differences between Brahms and Franz Liszt, in a sense the Leonard Bernstein of his day, were not only vast but also diametric. - Where Brahms was subtle, Liszt was obvious. Brahms was the introvert, Liszt the extrovert. Brahms tended to be enigmatic, Liszt was explanatory. Brahms was restrained and casual, Liszt was almost flamboyant and sometimes ceremonial. Brahms was the Classicist, Liszt the Romantic. Brahms could be almost angelic, Liszt almost Mephistophelian.

The Requiems of Brahms and Giuseppi Verdi, however, are, like their personalities and characters, so dissimilar that the only things they have in common are musical form and their religious subject matter. Verdi's work, operatic in the extreme, is marked by theatrical drama, while Brahms' piece is far more introspective and tender. Both these Requiems are among the greatest works of their kind, notwithstanding the marked differences between these men in religious outlook and musical approach. Dvorak, a simple, pious being whose Stabat Mater was inspired by the death of his own daughter, once said of Brahms, "Such a great soul, yet he believes in nothing."

As a man he seems to have compensated his outward lack of piety with an innate goodness, and personal charity, which often benefited others. Brahms was not a religious man in the strict sense of that term - but he retained the Christian ethic and its dictates specifically in the conduct of life.

Brahms' renown, even in his own day, fostered the evolution of a historical petri dish in which the culture of "The Composer" grew and flourished. It seems to have begun with Beethoven and was certainly perpetuated by Brahms' fame throughout Europe. Strangers acknowledged him in the streets of Vienna and his music was performed on different continents.

Sometimes fittingly called "The Keeper of the Flame," he was debatably the last true musical classicist. As the Baroque era ended with Bach, the Romantic age began with Beethoven and ended with Brahms, whose music was the zenith of its epoch. Influenced by Beethoven in some ways but not in others, Brahms chose the conventional architectural structures for his music, emotional in spirit but clothed in traditional formal garb. In its temperament, however, he was a Romantic: at times lyrical and heroic, at others meditative, dark and intimate, but usually with unmistakable overtones of a seething passion that allows an almost immediate identification of his music as having been composed by him, only by him, and by no-one else but him.

Brahms' work has an atmosphere that's impossible to define, difficult to explain, hopeless to imitate but very easy to recognize. What he accomplished in about forty five years of professional musical life represents in its qualitative magnitude a corpus of achievement that boggles the mind of the musician. The violinist Nadia Salerno-Sonnenberg is on record as having said she has a hard time believing that a human being could actually conceive and compose, without divine intervention, the Violin Concerto that came from Brahms' pen. He composed numerous piano, chamber and choral works, and though he wrote only fourteen compositions for orchestra (including the four symphonies), almost all of them are firmly in the standard repertoire. The importance of his musical contributions is immeasurable and his position in the history of music is virtually unique.

Brahms was fortunate: his creations outlived him and will outlive us. He didn't give the public what it wanted; he gave it what he wanted, and they accepted it on his terms. He broke no new ground in the handling of his materials, choosing instead to cultivate an existing garden, the seeds of which had been planted by the giants who had preceded him and whose steps he could still hear behind him. Throughout his life he remained an island in a sea of swells. With the possible exception of the even-then popular Hungarian Dances, he showed a conspicuous disregard of popular trends, producing works that were characteristically introspective and intellectually profound. There was nothing of the revolutionary about him, either personally or in his work - unless one considers his conservatism a revolt against the radicals. He might have agreed.

Had he lived even another fifteen years, posterity might have been graced with additional chamber and piano works, and even recordings of his own piano-playing. He may have eventually journeyed to Norway (despite his aversion to boat travel) at the invitation of Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg, who thought Brahms might find inspiration there for a fifth symphony. Though the likelihood is slim, he might even have visited New York, where Gustav Mahler might have given a Brahms Festival with some joint piano recitals between the two composers. An impressario wanted to take Brahms, when he was still a precocious child, on an American tour, but this never came to pass. Conjecture is fruitless but still fascinating.

* * * * * * * * *

Brahms was unassuming but he could also be facetious. On his arrival in Mürzzuschlag (pronounced "mee-YOORTS-tsoo-shlahg"), in the Styria region of Austria, where he spent the summers of 1884-1885 composing his Fourth Symphony, the already famous composer registered with the authorities as "Itinerant musician." Once when Clara Schumann stopped in Mürzzuschlag to visit him, he arranged in advance to have the entire railway station restaurant cleared so they could dine with each other undisturbed. Today, a journey to Mürzzuschlag from Vienna's Sudbahnhof (South Railway Station) takes about one hour; in Brahms' day, it took more than four.

The Dietrich House, where he lived, is now The Brahms Museum, the only such entity in the world devoted exclusively to him, and contains more original Brahms memorabelia than has ever been permanently displayed publicly in one location. The museum opened in 1991, 106 years late but certainly none the worse for it. Among the myriad authentic Brahms mementos exhibited are books from his personal library (including his red Baedeker guidebook), his coffee maker (a then state-of-the-art apparatus), along with one of the actual canisters in which he had his coffee sent to him in Mürzzuschlag, a glass wine carafe, some of his bow-ties (displayed as he himself would have kept them: in a disordered pile), and an ashtray in which rests the butt of a cigar said to have been smoked by Brahms himself.

The Museum's dominant exhibit is a concert grand piano made by Wilhelm Bachmann of Vienna ca.1850, which Brahms often played during his stay in Mürzzuschlag. Given the changes in piano construction even between 1825 & 1850, the Bachmann instrument has a timbre somewhere between that of the hammerklavier and a modern concert grand, leaning in the latter direction while retaining a direct sonic connection with the former. The sonorities of the Bachmann piano are closer than our modern instruments to what Brahms himself heard during his time in Styria. A gift from Dr. Peter Freiberger of Mürzzuschlag, the large Bachmann piano is displayed prominently in the Museum's recital hall, where performances are given on the instrument even today.

Perhaps the most significant of Brahms' pianos, which remained in private hands for decades, was made by J.B. Streicher of Vienna around 1865. This was the instrument Brahms had in his own Vienna apartment at Karlsgasse 4. It was displayed at The Brahms Museum during the Brahms Festival in the fall of 1996. The author had the unique experience of playing this piano, whose tone, befitting the nature of Brahms' music, is wonderfully smooth and mellow, and which offers us the sounds of an era that died with him.

During his second summer in Mürzzuschlag, a fire broke out in a carpenter's shop very close to the composer's dwelling. While everyone has an ego, it's the creative artist who acknowledges it more readily than do others, but Brahms' conduct on this day, and his subsequent deeds, are clearly not the mark of The Egotist. Having already fled from his desk in his shirtsleeves to join the bucket brigade, he impelled the stylish onlookers to lend a hand. Soon he was warned by a friend that the fire's direction was threatening his rooms - and the precious manuscript of his nearly-completed Fourth Symphony (now in the Central Library in Zürich, Switzerland). After a moment's pause, Brahms simply continued with his fire-fighting. The friend had difficulty getting the room-key from the busy Brahms, to get the irreplaceable score to safety. Ultimately, the ruined carpenter actually benefited from the fire, thanks to Brahms' munificence, which was both practical and anonymous, in keeping with his usual procedure in matters of personal generosity with those he didn't know.

* * * * * * * * *

Two of Brahms' idiosyncracies were his reluctance to put enough stamps on his letters, and to pay duty on what he smoked - cigarettes in his youth, later graduating to the cigar. Once he himself turned smuggler, but with unfortunate results. His first biographer, Max Kalbeck, tells how Brahms, before being graced with unlimited funds, hid a large quantity of his favorite Turkish mixture in his bag. He evidently thought he had an imaginative cunning that would deceive the smartest Customs sleuth. Brahms had an absolutely towering musical intellect, but his innocence in the practical matters of Customs logistics was woeful, and the masks of Pathos & Comedy were now worn simultaneously. At the border, to his dismay, the Customs officers unerringly homed in on something that looked like a disembodied leg. The composer had stuffed a stocking full of tobacco, under the naïve impression that no official would bother with such a thing. This caprice cost Brahms loud cries of rage a-la-Beethoven, the amputated leg, and a fine that corresponded to the magnitude of his music.

In Austria then, as now, protocol dictated that even the spouse of a titled individual share the distinction. For example, the wife of Brahms' friend, Herr Dr. Richard Fellinger, would be addressed as Frau Dr. Maria Fellinger. Brahms' widowed landlady in Vienna, Frau Dr. Celestine Truxa, was once called away for several days on urgent business, leaving her two young sons at home in the housekeeper's care. On returning she was surprised and touched to hear that Brahms himself had gone in every noon to see if the children had the right food, and every evening to see if they were properly covered. He, himself, had grown to young manhood in the Hamburg slums and as a young teenager had to supplement the family's income by playing piano for the sailors in the port city's brothels. He had little sympathy, though, for the children of the wealthy, feeling they were privileged enough in having been born with silver spoons in their mouths.

Brahms never allowed a score or book in his personal library unless he himself had already read it. His workroom in his Vienna apartment had a traditional kneehole desk, but his library contained a tall, console desk, rather like a pulpit, at which he could stand while writing. Personal privacy was a ruling passion with Brahms, and even secrecy played a role regarding his compositions-in-progress. This lectern-type desk had a raiseable hinged top. When a visitor knocked at his door, Brahms would raise the desk's lid and quickly conceal the manuscript on which he was working. Today this desk is displayed in the special Brahms Room at The Haydn Museum at Haydngasse 19 in Vienna.

Visitors to Brahms' Vienna apartment could have a hard time finding a place to sit. All the chairs were usually filled with books or scores, but the supreme order in his compositions extended to his personal sense of organization. According to his landlady, "He knew by heart the position of every single volume; and, on his travels, he might write to me to send him, for example, the fifth from the left on the second shelf from the top."

Like Beethoven before him, Brahms was sometimes negligent of attire. A composer has greater priorities than to maintain a reputation as a clothes horse. Brahms' occasionally unkempt appearance might be due to his prosaically practical method of "packing" for a journey, which was ingenious in its simplicity: he'd pile his clothing on a table-top, tip the table, and let the clothes fall helter-skelter into an open trunk. While his clothes may have needed pressing, they - and his person - were always spotlessly clean. His old brown overcoat, which should have been condemned years earlier, became even as he wore it one of Vienna's famous "landmarks."

Today three of Brahms' inkwells are exhibited in as many locations in Austria. - His clear glass inkwell - even now dried ink residue can still be seen at its bottom - is on display in the Brahms Room at the Haydn Museum in Vienna; his serpentine marble inkwell is at the Kammerhof Museum in Gmunden; and his bronze inkstand is displayed at the Brahms Museum in Mürzzuschlag. A staunch conservative and by nature a creature of habit, Brahms continued writing with quills even after they were long out of fashion.

Johann Strauss was held in very high regard by Brahms, who was a frequent guest at the Strauss home. Strauss' daughter, Alice, had a hand-held fan which when unfolded revealed the signatures of many of her father's illustrious visitors. Though himself averse to giving autographs, Brahms complied with her request to add his signature to the fan, which he did in an unusually clever and complimentary way. On the fan he notated a few measures of music - not his own, but the first bars of her father's Blue Danube waltz, below which he wrote, "Alas, not by Johannes Brahms."

Brahms' very existence was an effective testimony to how futile pessimism about art can be. No sooner had the Liszt-Wagner school of thought declared that absolute, "pure" music was played out, than Brahms appeared. In the 1890s Brahms was visited in Bad Ischl, Austria, by a young musician. Though Brahms admired the younger man's talent as a conductor, he didn't think highly of his "modern" music. "Music is done for," Brahms lamented. "Nothing new remains to be composed. You and your kind have seen to that with your compositions." As they crossed a footbridge the younger man gazed into the flowing stream and observed, "Master, I have just seen the last ripple." The young man was Gustav Mahler.

* * * * * * * * *

An unpretentious man, Brahms usually took the least expensive lodgings on his travels and took his meals at the least expensive restaurants. His earnings, wisely invested for him by his publisher, gave him the fortunate and very enviable practical stability to live very comfortably throughout his life, but also very simply, in line with his personal character, without the need to hold an official position. His estate, most of which he had bequeathed to the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien (Society of the Friends of Music in Vienna), was valued at about 400,000 Marks - an extremely handsome sum at that time and a handsome sum even now. There are intrinsic differences between cheapskates who are extremely stingy with others but who treat themselves like royalty, and the generous who are considerate of others less fortunate than they and who spend on themselves only what's warranted. Brahms was one of the latter, and his few personal extravagances were minimal and were the exceptions.

One evening he wanted to entertain his guests particularly well at a fine restaurant, and said, "Waiter, give us a good bottle of wine - but it must be your best." Soon the man reappeared with a bottle cradled in its basket, a venerable affair covered with cobwebs and dust. "What sort is that?" asked Brahms. The waiter bowed and said, "Our finest vintage, Master. It is `a bottle of Brahms`". The composer tasted the wine, pushed it away, tapped the label and said, "Well, then, you'd better bring us a bottle of Bach!"

As Brahms' contemporary Anton Bruckner often wore incredibly baggy pants, Brahms liked to wear his trousers unfashionably short. When his tailor was daring enough to make them the proper length, almost in defiance of the composer's orders, Brahms addressed this matter by assaulting the pants with his desk shears and just cut them to ankle-length. This was a wonderfully simple solution to this problem, but sometimes he cut and slashed without overmuch regard for the laws of symmetry. While both pants legs were shy of the ground, one could be noticeably shyer than the other.

On one literally historic occasion his trousers temporarily overcame their ground-shyness, but with results that were if not actually calamitous then potentially very embarrassing. Brahms' friend and colleague, the great violinist Joseph Joachim, was introducing Brahms' Violin Concerto in Leipzig, Germany, with the composer himself conducting the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. Unfortunately Brahms hadn't finished dressing properly. Arriving onstage in grey street trousers, it soon became evident he had forgotten to fasten the braces, so that as he conducted, more and more of his shirt was continually revealed between upper and lower garments. To envision what might have happened if the concerto had been one movement longer, takes little imagination.

Parenthetically, the old Gewandhaus concert hall in Leipzig was bombed during the Second World War. The original podium, replete with candle-sticks, from which Brahms had conducted (as did Mendelssohn, Liszt, Wagner, and so many others) was one of the few original articles from the old concert hall that was saved before its destruction. That conductors' desk is now on display at Leipzig's old City Hall - as is the inlaid table at which Johann Sebastian Bach signed his contract as music director of Leipzig's St. Thomas Church, where he spent the last 27 years of his life as the organist.

After attending the funeral of Clara Schumann in 1896, Brahms spent the night at a large estate on the Rhine. That evening he tried to take part in playing his c-minor Trio but he was overcome by grief at the loss of his friend, and had to stop after a score of measures. This loss marked the beginning of the end for Brahms, and he outlived her by less than a year.

We are all part of the chain that binds us to the world's history. The author was told by Elmer Bernstein (composer of the scores of the films "To Kill A Mockingbird," "The Ten Commandments," and countless others) that his own piano teacher at the Juilliard School, Henriette Michelson, guided him through his entire period of piano study. She had been a child prodigy in Vienna. When a young girl, she was taken to a concert where she heard a performance of the second piano concerto of Brahms - with the composer himself as the piano soloist. The man who cared for Brahms shortly before his death was Dr. Joseph Breuer - the very physician who gave Sigmund Freud the germinal idea that led to the development of psychoanalysis. Dr. Breuer's son, himself a physician, spent some time with Brahms during the composer's final hours. Those connective links seem even stronger when we realize it was only until relatively recently that people who actually knew Brahms were still alive.

* * * * * * * * *

Johannes Brahms accomplished more in a single year than most others do in their own lifetimes. The twelve intermittent summers he spent in the autumn of his life during the 1880s and 1890s in Bad Ischl, near Salzburg, were fruitful creative holidays. By that time he had already cultivated his famous beard, which he had grown in Pressbaum, Austria in the early 1880s, during the composition of the second piano concerto, arguably the greatest such piece ever written.

Though Brahms often met with friends for dinner at the Hotel Elisabeth (now a pharmacy, the D.M.Drogerie), or at Zauner's Restaurant (still a popular establishment), the dwelling he occupied in Bad Ischl was in a private house at Salzburgerstrasse 51, a short walk from the center of town, for his need for seclusion and privacy. We must remember that he had already reached iconic status as a composer and was the dominant musical figure in Austria, beseiged even then, before the era of mass media coverage, by autograph hunters. The house he chose was owned by the Gruber family, who rented the second, uppermost storey to Brahms and gave him the use of a Bösendorfer grand piano (now displayed in the Brahms Collection at the Kammerhof Museum in nearby Gmunden). The Grubers had a young son, born in 1875.

Brahms would compose for most of the morning and often part of the afternoon. During his first summers in Bad Ischl, when leaving the house Brahms would address the young Gruber boy, "Hello, child." As the boy grew older, Brahms modified his greeting to, "Hello, young man." He'd occasionally talk with the boy, asking him how he had done in school that year, and so on. - On his last day at the Gruber house in the fall of 1896, as the carriage waited to take Brahms to the railway station for his departure from Bad Ischl, the 63-year-old composer approached the now 21-year-old man, shook his hand, and said to him, "Aufwiedersehen, Herr Gruber" (Goodbye, Mr. Gruber). The passage of time and sad sequel have shown us that Brahms had cancer of the liver, and he might have sensed that he'd not return to Bad Ischl. Fate verified this: he died less than a year later, on April 3, 1897.

This vignette was reported to this author in the fall of 1987 in Bad Ischl, by the elderly lady who was then living in the Gruber house. The young boy whom Brahms had seen grow to manhood was her father.